Prospero Hall is back.

I’m sorry, that’s a lie.

2001: A Space Odyssey the Board Game is not a Prospero Hall title. It’s a Phil Walker-Harding design courtesy of Maestro Media. This fits right alongside quirky board game cuts like The Warriors, Fast & the Furious: Highway Heist, and Rear Window. I almost don’t trust the credits.

Like those comparable titles, this is a straightforward rules light experience. Humorously, it is far more accessible than the movie it’s based on. It does raise the question, who is this for?

2001 is a mind-blowing film. Its cinematography is exceptional, its emotional beats are prolific, and as an experience it is singular. This streamlined board game is none of those things.

To be clear, it’s not what one would call a cash grab. There was clearly effort put forth, and Walker-Harding did not take his foot off the gas. In fact, within the scope of this modest game, I’m surprised he’s able to squeeze as much nectar from the property as he has.

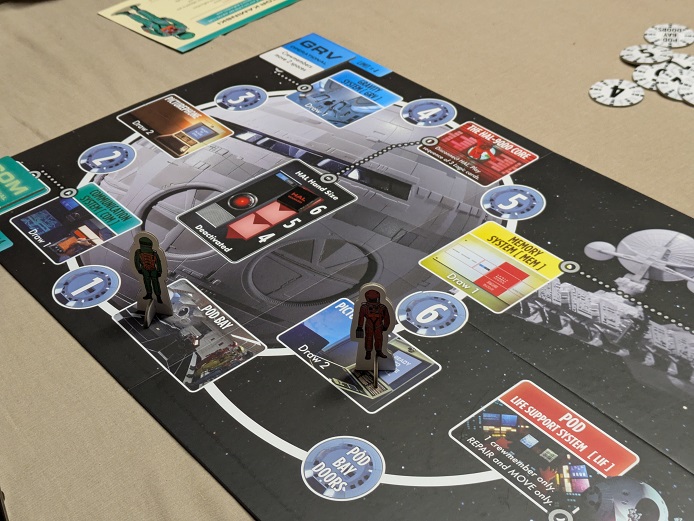

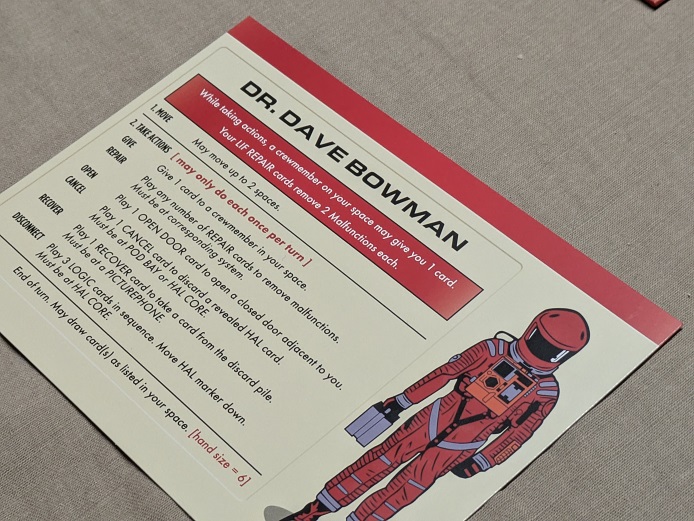

This game is focused squarely on the sequence where HAL turns on the crew of Discovery One, attempting to sabotage the mission to Jupiter. This is the role of the overlord player, a menacing position that observes, restricts, and isolates the team of astronauts. Those beleaguered pilots are portrayed by everyone else at the table. The many in the one versus many. They’re in a struggle for survival where they’re racing to assemble a proper code sequence and shut down HAL.

Everything is fueled through cards.

HAL’s deck is stuffed with malfunctions for various stations on the spacecraft. As an action, HAL can place one of these cards on the associated location and cause it to degrade. Break enough modules, or just the life support system, and the ‘nauts lose.

Meanwhile, the good guys are taking turns repairing this damage and nurturing their hand of cards. Amongst their repairs are numbered cards. Literally numbers, such as a 2 or a 5. If a player collects three numbers in a sequence – such as 7, 8, and 9 – they can turn them in at the HAL-9000 core location. Do this three times and the villain is deactivated. Game over, man. I know, wrong film.

All that’s the shallow stuff. The humming engine that is background noise. The pulsating turbine in the foreground is comprised of the unique touches found scattered in the special cards. Like HAL’s “Lipread”.

If Lipread is in effect, the player’s cannot speak. This is a large penalty as 2001: A Space Odyssey the Board Game is at its core about communication, observation, and subterfuge. To organize their hands and form a sequence of three numbers, player’s must spend actions to pass cards between themselves. They cannot show each other what they hold or talk privately. Everything must be said out in the open. HAL is always listening.

There’s a wonderful moment in this game where a new player stumbles upon an inkling of brilliance. They start trying to trip up HAL, to thwart the cold machine’s machinations. In one play, a protagonist said, “I have a card that is half the value of the card I gave you earlier, plus one.”

What bastards.

As HAL, a large chunk of the game is deduction. This is because you have two cards in your deck that allow you to guess at a sequence number a player holds. If correct, they must discard it. This is horrific for the astronauts as they may need to churn through their draw deck to reshuffle it in order to recover that lost number.

Once player’s undercover that first order of strategy, a surprising amount of tension manifests. In one moment, a player finished their turn but the group was still caught up in discussion. They were planning their next move, ready to make progress and push towards victory. HAL takes a single action in between each protagonist activation. It was my turn. I sat there, not acting but listening.

They didn’t notice. They kept talking.

After some deliberation and open planning, the next player began to take his turn. “Wait.” I commanded. “I haven’t gone yet.” They slowly realized I had been calmly listening the entire time.

Those moments are about the best you can hope for from this game. The climax of shutting down the machine before it guts the crew is reasonably well executed, with the decision often coming down to a photo finish. There are a couple of neat tricks such as locking an astronaut outside the ship, sealing them away from the other players. In fact, HAL can lock doors all throughout the ship, eating up time and energy.

There’s also a nifty mechanism where half of HAL’s hand is public, with cards positioned on the table faceup. This offers an idea of what the entity can do and it forces difficult decisions on the AI player as they can often choose what is revealed versus what is held privately.

During these glimpses of turmoil it’s easy to smile and fade into the design, appreciating what Walker-Harding has accomplished.

There are moments it’s not quite as good as it could be. For instance, HAL must hold one of his two number ganking cards in hand, for if the player’s know both have been spent then they can openly talk without fear of consequence. I was playing it cool in one session, intently listening and living my best misaligned artificial intelligence life. The players were fearful, cowering even. I executed my killshot at the perfect moment, forcing Dave to discard a precious “2”. And then Dave immediately played a special card to retrieve it from the discard pile, completely undoing my masterstroke. Boo. Gutting the tension with a functional counterspell really undermined any sense of threat.

Player count is also a touchy subject. It is competent at the lower end, but the need for discussion is much less. This harms the strongest quality of the game, and I’d urge you to assemble a larger group. The best junctures occurred with a full table, humans buzzing with a chatty cacophony that was beamed into HAL’s metal id.

The limited scope is prohibitive as well. This shouldn’t be too surprising. It’s the same ill that plagued Prospero Hall releases. These kind of skilled mass market titles have limited ammo. They’re certainly fun and can uplift a session, but they struggle with their long-game. There’s not enough strategic muscle nor enough compelling content to maintain interest beyond the near future. Those strongly affectionate for the intellectual property may be able to use their fandom as filler to make up for the latent cavity, but everyone else is best served as just sampling the goods instead of committing to them. Fortunately, these types of products tend to be inexpensive.

While I’m a pessimistic human, there was a part of my soul holding out hope this could do something special. I wanted it to be another Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Slaughterhouse, a game that was elevated due to experimentation and a strong artistic vision. 2001 the Board Game is not exactly that. But it is serviceable and interesting. That evocative framing of communication is as splendid here as it is in City of the Great Machine, and that’s enough to have entertained me for several plays.

One thing that I’ve thought a lot about is how this game sidesteps the issue of player elimination. This was a strong criticism of Ravensburger’s Alien game, a design of similar weight and style. That adaptation made it impossible for players to be felled by the xenomorph, and the end result was a complete defanging of the central foe.

2001: A Space Odyssey the Board Game doesn’t have player elimination either. But it still feels risky and unsafe. Instead of maintaining health for each player, it relocates your sense of self to your hand of cards. Not in the same way that Gears of War: The Board Game did it as your hand isn’t directly representative of your vitality. Here, your hand is representative of progress. Of the integrity of your mission. It directly correlates to agency and power. HAL attacks this, stripping players of their existence one card at a time. And it feels excruciating when an important card is bled. There’s a quite clever emotional resonance here without relying on physical danger, and it’s the most interesting and subtle aspect of this design.

The second most interesting quality of this release is not something found in the game itself, but rather discovered when taking a broader view of the industry. 2001’s publisher Maestro Media is making a move. Alongside this nice little tune, they’ve released games based on The Binding of Isaac, Hello Kitty, The Smurfs, Strawberry Shortcake, Clash of Clans, and more. They are accelerating their output and their intellectual property consumption is vast.

In a sense, they’ve become the new Prospero Hall.

One distinction is that Maestro is not relying on an in-house studio. They’re farming out the design to accomplished individuals. Shem Phillips, Eric Lang, and Phil Walker-Harding. This is an interesting move.

No one can argue with Prospero Hall’s success. While they produced a lot of games that best served to nudge the quality of mass market games higher, they also produced some white hot bangers. Texas Chainsaw Massacre remains their best effort, but I also dearly appreciated Rear Window, Jaws, and the original release of Horrified.

I don’t know if Maestro Media is capable of those inspiring singles. Nonetheless, they’re attempting to fill the void. The pathfinding has already occurred, and they’re in a good position to capitalize on this currently underserved market. Hopefully 2001: A Space Odyssey the Board Game is a turning point. There are glimpses of magnificence in this game and it’s closer than any other Maestro Media title I’ve encountered.

A copy of the game was provided by the publisher for review.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.