“Think left and think right and think low and think high. Oh, the things you can think up if you only try.”

Party games often get short shrift. But it’s a difficult genre for innovative work. The majority of titles in this category are word games springing off the popularity of Codenames, or selection and ranking activities riffing on Apples to Apples. Hits like Decrypto, ito, and So Clover fit the bill.

Things in Rings does not. It’s a non-conformist.

This oddball consists of a couple of overlapping rings placed in the center of the table. One ring maps to a secret rule about words and the other attributes. These hidden rules are drawn from a deck and known by a single player. This MC runs the game; they can’t win and have no goals other than orienting the experience.

Everyone else at the table is dealt a small hand of cards. These contain the things. Illustrations of a hammer or a toilet plunger or a sofa. Each is brought to life with a wonderful Dr. Seuss aesthetic courtesy of artist Snow Conrad. This silly surreality forms a throughline for the off-kilter experience.

On your turn, you select one of the cards from your hand and place it within one of the rings, or perhaps where they overlap. The thing belongs in a specific spot, depending on whether it follows the attribute rule, the word rule, or both. Or none at all.

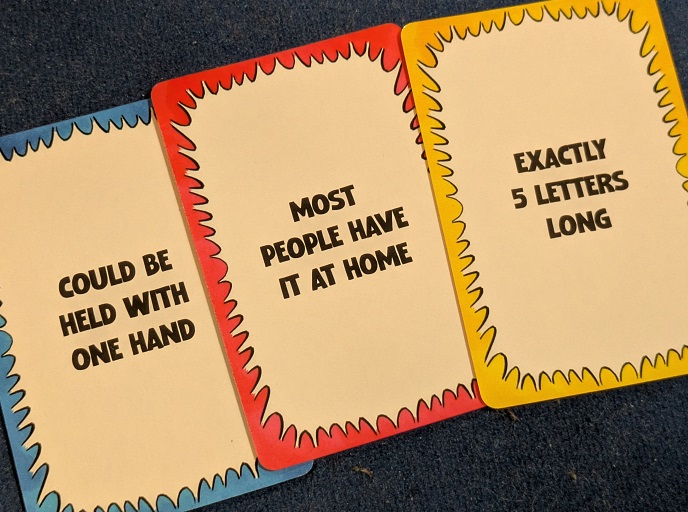

The rules are the tricky part. The game hinges on their efficacy and imagination. Word rules consist of things like “possesses more than one of the same vowel” or “begins and ends with a consonant”. These apply to the actual word on your card, which maps to the item pictured. Attribute rules are more interesting. Examples include “strong taste”, “floats in water”. and “usually round or curved.”

The MC adjudicates whether your placement was accurate, picking the card up and positioning it in the correct ring if not. If you were right, you get to go again. Otherwise, you draw a new card and your turn ends.

Much of the game master’s job is interpreting the absurd. Such as whether a rubber duck has a strong taste, or whether a skunk is round. Watching this person contort their face trying to square such nonsense is a humorous. The spectator pleasure runs both ways. The person in charge can smirk at people firing every last neuron in their brain as they struggle to interpret why a card was rejected from one ring and placed in another. This game will certainly wrinkle your brow.

The rule cards have a difficulty rating on the back, so you can tailor the challenge to the crowd. I’m a savage and prefer to draw them completely at random. The goal here is to be the first to empty your hand. Easy-peasy.

Adept students may be calling me out. All of this sounds vaguely familiar. Yes, that’s because Things in Rings is really a more inviting and warmer Zendo.

Zendo is a bizarre game. It’s played with semi-transparent plastic pyramids from Looney Labs. These neat pieces stack upon each other and allow you to make different triangular 3D shapes and patterns. Like Things in Rings, it’s all about deducing a rule owned by the player running the game. Zendo though can be maddening. The problem is that the master creates the rule freely on their own. This allows a wide latitude in creativity, but it also results in sessions where the rule is too complex or obtuse. It’s a weird game worth experiencing, but it’s cold and abstract and often exasperating.

Things in Rings is Zendo with far more leniency. The rules are pre-determined by cards, and crucially, the players don’t even need to fully understand them. That’s right, since the framework is placing your cards in one of the rings, it’s effectively multiple choice. The winner is often the best guesser.

This is designer Peter C. Hayward’s most significant offering in this work. It’s a more friendly affair, one where you don’t have to rack your brain in desperation. You can simply try to roughly match the pattern of previously placed cards and hope for the best. While the winner will usually have an idea of what the rule cards say, they often won’t know one of them or will only be partially correct. It’s hand grenades, not darts.

Bringing the Zendo experience to a wider audience is a clever twist to the recipe. But it’s also the design’s major flaw. By removing the necessity of identifying the rule in its entirety, the experience is reduced to a vibes-based casual exercise where success frequently seems unearned. There’s a generous failsafe where players can feel not as though they were outplayed, but as though they were out lucked. This is not great for the longevity of play. In distancing the activity from nuanced deduction, the stakes are lowered and investment is reduced. With flattening the sharpness of Zendo, it reduces the cover charge for entry and in parallel lowers the degree of satisfaction.

Things in Rings heavily relies on its gimmick. For those unfamiliar with Zendo, it feels novel and weird in a delightful way. It’s one you want to show people. “You haven’t played Things in Rings? Let’s fix that.” There’s a compelling vicarious nature to this sort of play which necessarily limits its tail.

It does produce some fond lightbulb moments. Those times where you place a card in the correct position and you think you’ve figured it all out. Sometimes those occurrences get dashed when a new card violates your hypothesis, but sometimes they don’t.

One great feature of this title is its adaptability. If the competitive mode doesn’t do it for you, perhaps the cooperative format will. This is played similarly to the standard approach, but all of the players must empty their hands before a set number of rounds occur. Discussion is open and free-form. Everyone will be chiming in with various ideas on what the rules can be. It’s less quiet and cerebral in this mode, which may be appreciated as a more proper party game.

Difficulty can also be widely tuned. Beyond the rule cards being segregated by rating, players will also want to add the third “Context” ring relatively quickly. This adds a third rule, one which is more enigmatic than the others. “Most people see it regularly”, “useful”, and “can be dangerous” are some of the options.

Can a yo-yo be dangerous?

The difficulty with Things in Rings is that it’s less reliably satisfying. It’s less raucous. It’s mindful and contemplative, but also whimsical and careless. There’s a glimmer here in its main conceit, the derivation of Zendo, but it’s the type of thing that has an expiration. Maybe it’s cheap enough that this isn’t an issue. Give it a kick and then pass it on to someone else, like an appreciated novel that wants to be handed off to a virgin soul. Or maybe you just play it a few times, give it a philosopher’s nod, and then tuck it into the back of your shelf behind all those other games you never play.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

100% YES! A yo-yo is dangerous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! I would agree.

LikeLike