I remember the first time I saw The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. I was a teen, sitting in front of a small CRT in a small living room. I was wholly unaware of what the next three hours of my life would entail. I hadn’t yet learned to trust my dad. And while our relationship is complicated and full of doubt, I’ve since realized not to question his taste in film.

This movie changed me. It rattled my brain. I didn’t know it at the time, but years later I would come to recognize it as the best picture ever made.

Released in 1966, it’s one of the defining Spaghetti Westerns and stands as the third feature in Sergio Leone’s Dollar trilogy. A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More are fine films, but they’re not the grand epic that this final installment is. Not even close.

Western Legends is not the best board game ever made, but it certainly is among the best of its ilk. This 2018 title was the debut of both designer Hervé Lemaître and publisher Kolossal Games. Served as a sprawling adventure, the design explores genre concepts established by titles like Runebound and Merchants & Marauders to present a sandbox framework for players to forge their own story via emergent narrative. Eight years and multiple expansions later, it remains the most significant work of its creative team.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is a poetic yet brutal film that deconstructs its genre. Western Legends brandishes a similar spirit in breaking down and reconfiguring its influences. Both warrant a critical gander.

The strongest connection these two works shares is theme.

Sergio Leone directed five Western films. They all contain a focus of deconstructing the romanticized genre by viewing morality as a continuum. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is the pinnacle of this ethical worldview, and the strongest lens to view it. Instead of adopting the traditional archetypal framing of the good versus the bad, Leone presents characters that display various moral ambiguities. While Blondie is explicitly named as the titular “Good”, he also is the man that guns down innocents in his very first scene. The man that frees a heinous criminal and profits off his wrongdoing. The man who leaves another soul in the desert to waste away. He’s a liar, cheat, and a murderer. His title is, at least partially, satirical. Tuco, “the Ugly”, amid all the violence and chicanery, offers moments of humanism. He shows loyalty to his brother, Pablo. He nurses Blondie back to health showing a sense of compassion under his veneer of selfishness. Even Angel Eyes – yes, “the Bad” – lets his mask slip briefly as he expresses sadness for wounded soldiers.

Nothing is clear or easy.

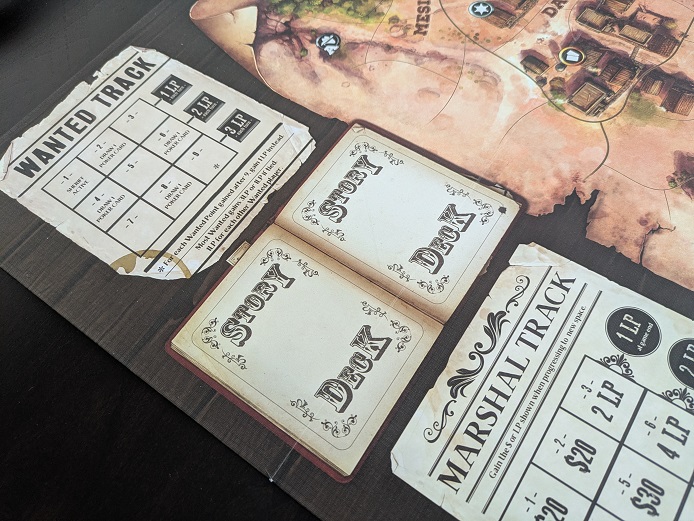

This is the creed of Western Legends. The game’s moral center is illustrated by two tracks. One is the Marshall path. It allows players to pursue a lawful and just career. Perform deeds of service, such as apprehending criminals, and your moral progression is visibly reinforced. At the opposite end of the continuum is the Wanted track, a tidy meter to capture your status as a vile sore afflicting the land.

What’s crucial about both of these routes is that they incentivize and even force movement. Western Legends is about momentum, both in morality and in action. The farther you push along each of these tracks, the greater the reward. There’s an almost cruel allure of pulling you farther and farther down a tunnel; your soul constricted with every step. Not only do your successes result in advancement, but your failures can completely reverse your trajectory. The wicked bank robber apprehended, overcomes their plight and finds righteousness. A Marshall, toiling away on the frontier sees an opportunity, and now they’re the ruthless train robber. It’s all so goddamn dramatic. It’s all so Leone.

A huge propellant in all of this is greed. The buried Confederate gold in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is the impetus for the narrative. Avarice is the primary motivation of each character. Near the climax of the film, Blondie states, “Two hundred thousand dollars is a lot of money. We’re gonna have to earn it.” This is the movie, right there. The secret of the unknown grave, the partnership of Tuco and Blondie, and the unrelenting pursuit of Angel Eyes all circle around this glimmer like buzzards in the sky. Every single scene can be torn down to its gilded studs.

This essence abounds in Western Legends. All actions have a throughline to wealth. Bank robbing, gold mining, cattle driving, poker playing, steer rustling, it’s all buzzards chasing the scent. Oddly, you’re artificially limited to how much cash you can carry. This, like those aforementioned moral tracks, is a springboard for change. You’re forced to head back to civilization and deposit your gold. Or spend it. You can’t ever rest. Stall and you will fall behind the pack. The thirst is endless. You’re gonna have to earn it.

Earning it, is very much an individual task. There’s a rugged independence to The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly that isn’t always persistent in the genre. My second favorite Western, The Wild Bunch, is about a group fighting for their way of life in a world that’s leaving them behind. It’s about camaraderie and brotherhood. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is a buddy movie concerning intense loyalty and sticking together up until the last frame. The Searchers focuses on groups clashing, on civilization versus the wilderness. Unforgiven, friendship and justice.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is about independence and selfishness. You can only count on yourself. Rely on someone else to shoot the rope? Eventually your time comes. Find yourself in a momentary alliance? Then your partner secretly unloads your gun in the middle of the night. Share a secret about the name on a grave? Say a prayer for Bill Carson.

Western Legends, likewise, offers no quarter. You can’t team up or form an iconic duo. You can’t work together to bring a villain to justice. It’s cutthroat individualism where everything is zero-sum. I wish there were opportunities for partnership, but that’s not part of the game’s creed.

While these artifacts share striking similarities, there is a key thematic component of Leone’s work that is missing in Lemaître’s. The legendary director considered The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly an anti-war film. He was fascinated with the Civil War and deliberately used it as the backdrop for the story. This environment highlights the futility and waste of war, portraying it as an entirely useless endeavor in several important sequences. Soldiers are not depicted as heroic, but instead are shown as beleaguered, fragile, and maimed. The parallel motifs winding throughout the film coalesce in a somber yet important scene where Blondie places a cigar in the mouth of a dying soldier. It’s a moment where all of the bombast retreats and we’re left watching a man’s soul slowly fade.

This is one of the weakest areas of Western Legends. It contrasts in this manner with Merchants & Marauders, a glorious sea-faring adventure in the height of the age of piracy. That game is set in the Caribbean, and one of its strongest elements is that the environment is unpredictable. Nations can enter into conflict with formidable man-o-wars appearing in the ocean and terrorizing the seas. The world feels alive, as if you’re existing in an external reality. Western Legends has little of that. It instead relies on the players to drive the action. I can foresee an alternate design where the Civil War makes an unexpected appearance, dynamically shifting the environment and shaping the narrative. Several new themes could have emerged, including Leone’s intent of criticizing the conflict.

I suppose no film and game will ever perfectly overlap.

Subject matter is the primary connection between this cardboard and cellulose, but there are a couple of other interesting junctions.

There’s no real equal to a movie’s Director of Photography in board game production. Artist, indeed, seems the most obvious parallel. Roland MacDonald did great work here. There’s a historical and cinematic panache to the various illustrations and painting style. While I would have preferred a grittier aesthetic when it comes to character and prop design, the work comes to life in its panoramic state with the board and all its various details laid out. When you add the sideboard from the Ante Up expansion, there’s an almost widescreen effect to the geography of the game. It stretches the width of the frame and buys a sense of scale that is wonderful and emblematic of its film influences. This credit is not only due to the artist, but also to the production and gameplay design. How the areas are laid out and traversed, how the general store is a small shelf with its sundries lined up to peruse. There’s intentionality, not unlike a DP establishing the look of a film.

Additionally, Leone’s directorial style makes an appearance in a more abstract state. In The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, he favors extreme closeups juxtaposed with wide panoramic vistas. This is best displayed in the climax, where the camera lingers on a distant shot of the three characters standing in the center of the cemetery. It then cuts to alternating views of each gunmen’s face, their eyes forming the center of focus. This wide to tight methodology is evident in Western Legends, just as it is in virtually all adventure board games.

On the tabletop, the contrast is initiated through macro-level activity, such as moving about an abstracted space representing your protagonist crossing desert and barren land. You perform high-level upkeep such as drawing cards, organizing your player mat, and second order maintenance like moving the train across the track that loops the board. Then, during your turn, the game sharply cuts to first-person action. A duel between two foes. A bank heist at dawn. A moment of tension as you resolve an event token. Activity transfers from narrative engagement, to mechanical resolution, to semi-simulative knock-on effects such as suffering wounds and stealing gold. The camera holds a tight frame, and you suddenly ignore the rest of the board, intent on the scene currently engulfing the shared game state.

It’s all organic and just flows. Like cinema.

What about the score? Ennio Morricone is a legend. From the moment we hit Sad Hill cemetery and the orchestra swells as Tuco runs among the headstones, all the way through the climactic gunfight, it’s pure cinematic rhapsody. There’s nothing like it.

Western Legends doesn’t have a soundtrack. Or does it?

A film’s score serves as an emotional backbone to the visuals. It’s woven with the blocking, framing, color grading – all of it – to enhance the experience. All elements function in unison to capture the viewer and deliver a particular feeling. Western Legends has such an emotional spine: the action deck.

This central deck of cards combines standard poker values and suits with explicit bonus actions. These are spent for nearly every action. To put a slug into another person’s gut. To play poker at the saloon. To apprehend a bandit hiding in the hills. Some of them possess powerful alternate actions such as moving far across the board or to gain bonus victory points. Occasionally you can alter the outcomes of shootouts or nudge probability in games of chance. The way they flow into your hand, are carefully considered, and then spent in bursts of action during pivotal moments – it’s all music. The tempo crescendos and decrescendos at various moments. The tension swells. There are unexpected movements and runs of colorful notation. They’re integral to filling out the experience and suffusing it with feeling.

Western Legends bears the same sense of meticulousness and passion that is evident in Sergio Leone’s masterwork. This passion is found in the game’s visuals and systems. It’s not as powerful as its paired film, but it is one of the strongest adventure game designs and a well-orchestrated effort. Like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, as I dwell on the experience it presents, my admiration continues to grow. That’s the beauty of cross-media analysis and artistic evaluation – the more we expand our boundaries, the more we expand our senses and mind, the more we are. The more we become.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

A couple decades ago I used to play a MMORPG on a private server, huge world populated by 3, sometimes 8, or, if you’re really lucky, up to 12 players at a time. I remember being excited by the possibilities of all the things I could do all alone, while also maybe perhaps sometimes catching a glimpse of another player. It took me some time to figure out all I can do is grind, and other players are so few they might as well not exist.

Western Legends gave me similar feelings. There’s a big world that’s empty and lifeless, and a plenty of places where you can grind without ever crossing anybody’s path. I felt that the core system has very few incentives for players to interact, almost nothing they do ripples to others, and events that are supposed to pit players against each other seemed quite artificial to our group.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. I felt there was far more incentives than is typical of this sort of game. If a player is mining gold and doing very well, you are hugely incentivized to rob them and go outlaw. Which then has knock on incentives of pushing people into going Marshall and arresting you. The delta in points via interaction can be large, and you also can gain victory points by dueling other players.

Overall though I do agree that interaction is not high. It’s not all on the same level as a skirmish or area control game. But I find more interaction here than in Merchants & Marauders, Runebound, Xia, Fallout, etc.

LikeLike

I agree that Western Legends feels certainly more interactive than other sandbox games (and we indeed had a lucky gold digger robbed on his way to the bank). Nevertheless, it still felt quite lonely for us, so I would definitely prefer even more interaction, direct or otherwise.

LikeLiked by 1 person