Descent has been a constant in the hobby since 2005. Its lineage stretches back even farther, as it functionally carries the torch for 1989’s Heroquest. It’s a comfortable reassurance that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Not anymore.

and you want more

Some view Legends of the Dark as a harbinger of doom. This is still Descent in spirit, but it’s a far leap in a certain direction – I’ll call it forward – as it’s taken our analog comfort food and modified the experience to exist with interdependence on that piece of technology in your pocket. There is quite a bit to discuss with this game, much which extends and lives outside the required application, but that is of course the focus of discourse because our phones and tablets serve as such a strong source of both excitement and pathology.

This design is really progressive in many ways. Let’s talk about those first.

Technically Graduated

Legends of the Dark advances the genre by reducing maintenance and busy-work while escalating wonder. There are no tokens littering the board and cluttering up the visual space. Enemies can be afflicted with statuses such as slowed or exposed and it doesn’t require a chit or card. Their wounds are also monitored and adjusted via poking the screen.

It stretches beyond that.

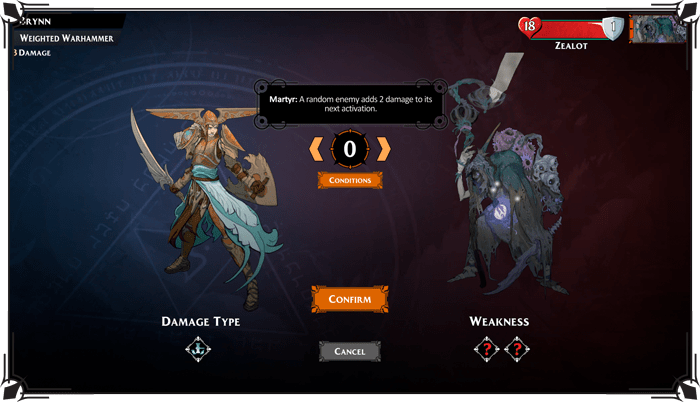

AI behavior is something occurring in the background. You don’t have to build a deck or follow a flow-chart. The inhuman processing also buys greater complexity of behavior. I saw this in a recent scenario where the enemies focused on a specific hero who was carrying an item of narrative significance. This is also seen in how quite commonly foes telegraph powerful abilities through text. A zealot may start chanting for instance, signaling a powerful spell which will be unleashed in the following round. You can actually learn this behavior and prepare for it.

Most of this is not particularly groundbreaking on an individual level, but it does emphasize that the technology is being used in service of the game as opposed to the other way around.

such a clean machine

Exploration and discovery are handled expertly. New corridors and rooms appear, but occasionally existing tiles or objects shift. You can interact with all of those glorious 3D pieces such as boiling cauldrons and disordered bookshelves as they each offer their own rewards and exposition. There are substantial surprises encountered in the campaign that have jolted my brain, things that wouldn’t have landed or functioned quite the same way if provided in a scenario book or through card draw.

Much of this will sound familiar if you’ve played either Mansions of Madness 2nd Edition or Journeys in Middle Earth. This is because Legends of the Dark’s app is an iteration on those two prior versions. This means it feels a little less revelatory in practice as I quickly fell into familiar steps triggering sight and exploration tokens, tapping successes into the UI, and bracing for enemy reprisal.

But all of that is just what’s going on inside the dungeon. The most conspicuous divergence from the past occurs outside the oubliette.

Between delves you’re travelling a very simple world map. It provides the function of geographic context – one of several actual efforts to legitimize Terrinoth in this design – but it also produces little interludes of random encounters. Then you get back to town and the real torture fun starts.

I really love the things that you do

The town phase of the tabletop dungeon crawler has been a tradition since Warhammer Quest. It can be a very enjoyable breath of fresh air where you can slow the momentum of play and reflect upon the horrors and joy your intrepid group has encountered. Some games have completely ignored it, preferring to focus on action and cut out this perceived fat. Legends of the Dark, as it does with many other institutional norms, rethinks the process entirely.

This is both boon and bane. The best bits involve taking stock of what you’ve earned on previous quests, including gold as well as all kinds of random junk with obscure names like Fortunos. You take those elements along with more mundane stuff such as bone and leather to craft recipes that you’ve found. These produce weapon modifications that provide new special abilities.

So after finding an appropriate recipe in an old tome, you scrounge up or buy enough material to craft that new pommel for Bryn’s sword. Now, whenever you attack there’s a 15% chance to heal a wound. Just like that.

This is fantastic. It creates character ownership, asymmetry across combat abilities, and the opportunity for specialized roles. All of the math is handled by the application and it sits gently on the surface of your tactical considerations. When they trigger it feels just like you’d expect from our extensive experience with this mechanism in MMOs and RPGs. One of my early surprises with this design was how much I enjoyed this crafting aspect and how each programmed random occurrence made my heart flutter and pulse quicken.

though your many years away

What’s difficult to hide from, however, is how stodgy this process can be within a group. Jim can’t just spend all of our bone and Aethnos without a discussion being had, unless of course he’s a selfish bastard. So there are speedbumps that can draw things out and severely halt progress. I’ve benefitted from multiplayer sessions where decisions were made without too much mental processing or disagreement. Comments such as “hey, can we craft a new component for Chance’s claws which haven’t been upgraded yet?” are common, as is everyone nodding along.

Some people will care very deeply about considering all 10 of your current available recipes and comparing the effects of the craft to existing weapon capabilities. With six available characters and 12 total weapons it can grow to a position of excess. This level of examination is far from a requirement as the game’s scaling difficulty does not punish you severely for undeveloped expertise in this area. Whether this ultimately is an unassailable complication will entirely depend upon group outlook and attitude.

Physically Affluent

Once you push past the app discussion and start searching for the rest of this game’s truth, the natural conclusion is to focus on the sheer physical presence. This is one of the easiest products to photograph that I’ve ever seen. Pillars, archways, tables, bookshelves, stairways to multi-storied dungeons, this thing is as beautiful as they come.

spreading his hand on the multitude there

The pieces themselves are sturdy and striking. They take some work to assemble but it’s not terrible at all. The overall visual impression reminds me strongly of Core Space, one of my favorite games of the past few years. Descent has an advantage in respect to setup, however. That is a significant pain point that Core Space never adequately addresses, although the bliss of play outweighs the hindrance.

Legends of the Dark deals with this problem by parceling out setup across the entirety of the adventure. Since exploration is such an integral aspect of the experience, putting a new tile or two out along with the various decorative terrain is not at all cumbersome. It’s actually an appreciated pause in the action that emphasizes the significant quality of mystery provided by the app. This is the primary intersection between the physical reality and its software support. We never quite know what is going on behind the scenes and have little sense for the algorithm evaluating our decisions. There’s potential here for sophisticated interaction, particularly when stretched across the length of a 15 scenario campaign, but it’s relatively impossible to deduce the efficacy of such an apparatus. That’s part of the appeal.

The miniatures serve in direct support of the heightened 3D presence. These are the absolute best board game miniatures I’ve ever seen. They come close to rivalling Games Workshop product and they require no assembly on part of the consumer. It’s remarkable and must be recognized in any proper discussion.

don’t take it away from me

The final physical quality I want to dig into are the floor tiles. I adore them.

I’d wager you weren’t expecting that. They are surprisingly austere with few details and what specks of ornamentation do exist seem to be out of scale with the miniatures and terrain. Criticizing their artistic validity is fair, and warranted.

But everyone seems to be ignoring their delightful geometry. Every crawler seems to offer the same few squares and rectangles. Not here. These odd configurations, supported by the various underlays, allow for environments that feel unusual, perhaps even exotic.

This is important because it interlocks with the 3D quality to form an actual sense of space. This is experienced in the very first scenario as you enter a keep, transitioning from outdoor tiles to an entirely segregated indoor section of the map. The elevated stone platforms and outstretched sections provide a strong context of place. It didn’t require any directed effort for grey matter to fill in the outside walls and the impression of height as it organically manifested.

It was there. I felt the contours and weight of the thing as it stretched from the table and tore a hole in the sky.

This is such an important aspect of the design and how it feels to play this newfangled Descent. It speaks to the utility of the 3D peripherals and their overall effectiveness. This is not window dressing or gimmick, it’s actual synthesized gameplay.

Of Rhetoric and Myth

The writing is actually the most difficult area to assess. It’s important to recognize that when discussing this there are actually many different domains of influence being grouped into a larger whole.

Let’s take the dialogue for instance. This is probably the aspect that immediately comes to mind. I would recognize it’s not terribly strong at times. The characters are obvious tropes and their chattering is mostly surface level commentary aimed at a very general audience. This makes sense from a product perspective as it allows the game to be experienced by a wide age range.

The real cost is the discomfort in orating to the table. This is nothing new, nearly every story-telling title requires reading paragraphs in various quantities. The difference here is that there is animated dialogue on screen between characters. This produces a situation where one player is likely reading aloud to the others, but it can be awkward trying to either roleplay the varied cast members or meta-narrate who is talking. Projecting the image onto a larger shared screen seems ideal, but it’s still not quite a smooth experience as everyone reading in silence feels wrong. What happens is that someone still must read aloud to keep rhythm and time.

Obviously this isn’t a hindrance in solitaire play and this game works extraordinarily well in that format. There are other issues with that playstyle, including the temptation to not setup each and every section of the dungeon or all of the 3D props. I wouldn’t say this is a common consideration, but there are times when I felt as though my troupe were on death’s door and not going to make it, so why fully setup that next room when I can just click through to the enemy attack phase and end the session.

This is primarily a problem in solitaire play because the physical assets are performative in nature. As I argued earlier, this is an integral element to the overall experience, but as the audience shrinks the necessity for spectacle also diminishes to a degree, even if just slightly.

The amount of reading is heavy overall, particularly when outside the dungeon, and it certainly outstrips the standard crawler. It never broaches Midarra levels of text but it’s certainly closer to that touchpoint than to Gloomhaven.

and keep good company

While I’m not enamored with the dialogue itself, I am fascinated with the nature of the story. The overall plot is adequate, but the story itself is very much character driven. Oh, and what a great and diverse set of characters we’re given. This is the first dungeon crawler I’ve played where I actually have a level of personal investment in these people and I know each and every cast member’s name.

Think about this for a moment and see if you can remember more than a character or two from Descent: Journeys in the Dark – that is Descent 1st edition. Many titles in this genre don’t even bother to name their protagonists, instead adopting a guise of light player authorship where you project a self onto your character and then must be satisfied with existing outside of the story you’re participating in.

Because Legends of the Dark is so character focused it accomplishes a level of investment that is completely unexpected. Combine this with the immersion of the physical dungeon, the visualization provided by the overland map, and the character interlinked plot and we have an unprecedented realization of Terrinoth itself.

Look, I’ve played Runewars, Rune Age, Heroes of Terrinoth, Runebound, and others. Terrinoth never existed. At best it was green and brown blob at the edge of my vision.

Legends establishes Terrinoth and integrates a grand narrative within its borders. One of the most stunning moves in support of this is presenting you with bi-lateral moral choices framed from the perspective of each character. Each persona is presented with two diverging story paths realized over many narrative beats in the campaign, forcing the players into tough moments of ethical crisis. The fallout of these decisions informs elements of the overall quest and leaves an indelible mark upon the story. It’s riveting.

Over my 15 hours with Legends thus far, I’ve come to actually care about these people and places. That’s damn remarkable.

The second aspect of writing that I want to cover is the scenarios. This game features some of the best mission design I’ve seen. It’s inventive and full of surprise. Every encounter feels strange and particular. With a pint in my hand and a fire at my feet, I can recall each adventure with vividness and clarity and spectacle.

This is one of the areas where it really sets itself apart from the competition. Gloomhaven is an accomplished title deserving of accolades, but it suffers from scenario design with a quality of uniformity. Sword & Sorcery comes close to replicating the sheer creativity here, but even then it never hits the highest of notes and is surpassed.

I could speak in great depth upon this particular achievement but it would spoil some of the game’s best moments, so I must retire that train of thought.

I will, however, point out that this is one of the few campaign dungeon crawlers that actually understands the cost of failure. By not forcing you to replay scenarios when you lose it buys a great deal of goodwill and retains a level of mystique concerning the inner workings of the app. If I was forced to replay a mission then I would be able to poke and prod the thing a bit more like a frog whose innards were spread apart in a science lab. Instead we’re kept in the dark and guessing.

Metaphysics and Theater

Legends is a singular experience. It has the potential to impart something profound and revolutionary, but it’s also positioned precariously. If one of the various elements doesn’t meet expectations then the co-dependent system is likely to destabilize.

This is most evident with the app. There is an unspoken burden in managing the input during play. You are constantly switching your focus from die rolls to user interface, from board to screen, from miniature to text. There is a level of fatigue which can set in over long sessions and attempting to push through it can curtail the strengths of the design.

Those qualities result in a need to avoid rapidly blitzing through the campaign. The novelty wears off with heavily repeated play in a compressed schedule. The experience works best as a weekly event where excitement and anticipation remain elevated.

Is this just fantasy?

For all its challenges, Descent does an exemplary job of minimizing the afflictions of app-based play. There is an extraordinary theatrical fusion between all of the various elements that forms a metaphysical experience I would describe as transcendent. It’s bombastic and operatic. It’s the closest thing to magic I’ve seen on the tabletop.

A key component of this accomplishment is that aforementioned sense of presence. By establishing an immersive 3D environment full of atmosphere and interest, it successfully wars for your attention drawing you back from the app and keeping you attentive on the physical arena.

This is supported by the absolutely wonderful combat system. Yes it’s dice based and there is the holdover of spending surges and acquiring fatigue, but the big evolution is flipping cards. Nearly every card is double sided; your weapon, your skills, even your character sheet. As you spend fatigue to trigger abilities or convert dice symbols to successes, you place them on the various cards as a cost. Conditions you acquire, such as terror, will also be placed on these cards.

As a tactical decision you will choose when to flip these cards. Turning the card over reveals a new ability, but more importantly it clears all of the tokens. This is a very simple mechanism but there is a surprising degree of depth and consequence.

For example, an enemy unleashes a powerful spell and inflicts poison upon one of your cards. Poison inflicts a point of damage every single round. No sweat, you can toss the token in the bin by spending one of your three actions to flip the card. The problem is that you just acquired a Focus token on that same card. This can be spent to re-roll a die and you’ve spent the last two turns maneuvering into position to strike down the menacing blood witch. Do you take the poison damage for another round or spoil the Focus token and turn the page? What if it’s your weapon card and you don’t want to flip your hammer to reveal your crossbow?

Choosing where to pile up fatigue and where to place status tokens can cause ripples throughout an evolving combat. Much of this nuance is not evident until you unlock more skills over the arc of the campaign and start juggling increased abilities and flip effects. It can become surprisingly satisfying chaining powers together and syncing them up for more dramatic maneuvers.

This fantastic mechanism manages just the proper amount of complexity, It’s simultaneously simple to internalize while still providing thoughtful tactical decision making. This works in combination with those wonderful environmental features to retain focus on the analog stage.

That war for focus is an indefinite struggle over the course of play and the game does a terrific job in that plight of competition.

I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about fiddliness in relation to this design. As I touched upon earlier, one of the largest benefits of the app support is the reduction in all of the administrative tasks. Of course it’s not entirely absent as much of the interaction has been transferred to the UI and some of it has been rolled up into the card flipping mechanism. But on the whole, it’s vastly reduced.

Playing this within close proximity of Sword & Sorcery provided for a significant degree of whiplash.

When looking at the dungeon crawl genre historically, and to some degree the American style of thematic games as a whole, it’s tempting to declare that a significant portion of the experience is rooted in administration. I don’t state this pejoratively, but there’s a concern that without a certain amount of component shuffling and manipulation there may indeed be no game. So much of the analog experience resides in touching things; rustling cards and tokens through your fingers and across your palm. It’s very interesting to examine what’s left in absence of all that fidgeting.

What I’ve found with Descent is that the void is filled with bewitching immersion. This is predicated entirely on that metaphysical struggle between the electronic and physical world and how it’s ultimately reconciled.

As you can see, I’m really flabbergasted with this one. The only significant criticism I’d levy against it is found in the difficulty scaling. The standard setting is too easy, gutting some of the desired tension in this type of game. Stepping up to heroic provides for a suitable challenge with a roughly 40% failure rate.

The problem is that it really draws out the most undesirable aspects of the genre. Instead of attacking with more clever patterns or with more dramatic damage scales, enemies are given a larger pool of health and more staying power. Since character growth is more incremental than steep, this results in grindy conflict that delays all of the wonderful bits. Because of this I’ve resigned myself to playing on normal and just living with the occasional lack of threat. This can of course be tweaked over time by the design team, but I’m not confident a proper intelligence can be integrated at this point. There are simply too few vectors for enemies to really scale with ingenuity.

I feel as though I’ve said too much and I’ve not said enough. This is one of the most storied titles of 2021 and it’s certainly divisive. While the application is not an entirely new integration, I am utterly shocked that one of the industry’s most prolific and corporate of publishers is actually taking a substantial risk by releasing such a progressive and costly product. And it’s doing it all straight to the retail sector without the intervention of Kickstarter.

In some respects, Legends of the Dark can be compared to Queen’s A Night at the Opera. Descent has reinvented itself and broken away from a constantly adhered to formula. Critics at the time described that album as “pretentious and irrelevant”, as well as “pretty empty, all flash and calculation”. Cretins are coming out of the woodwork frothing at the gill to issue similar condemnation to this work from Kara Centell-Dunk and Nathan I. Hajek.

Now, Queen’s masterpiece is regularly listed among the top albums of all time by those very same outlets that demonized it. When looking to the past, what will people think of Descent: Legends of the Dark?

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my efforts, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting my Patreon.

I’ll never buy a “board game” that requires an app. I don’t want to fiddle around with an electronic device while playing (isn’t there already enough digital distraction at the table without it being integrated into the game?) – and even if I did, I don’t want to worry about the app not working in three years. The whole thing just feeds into the increasingly disposable feel of new board games that has spilled over from digital gaming.

But even if this thing had no digital component, I’d still be skipping it. If I’m going to get into setting up terrain and tracking rosters and all that, I’ll just play a skirmish miniatures game like Frostgrave. I, too once had the boardgamer’s fear of rulers and LoS, but there’s really no substitute for getting your head down on the table and seeing what your little plastic dude can see. That’s immersion!

Still, I’m hoping that this version of Descent will provide what the last one did – an opportunity to scoop up a bunch of minis on the cheap when owners fail to get it on the table and clear it out of their collection. 🙂

LikeLike

It’s been very successful for them and they’ve already announced an expansion. I’m sure there will used copies on the second hand market, but I’m not sure it will drop more below $100 USD here.

LikeLike

Great review. What are your thoughts on complaints that this game has no meaningful decisions once the novelty wears off?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had played 7 scenarios, roughly 12-15 hours prior to the review. I’ve played it a couple of times since, but other games have distracted me.

Meaningful decisions is tricky. How you manage flipping your cards and managing your skills certainly are meaningful decisions, but this isn’t a terribly deep game. It’s more about exploration and the narrative than strategic approach. It’s certainly no Gloomhaven.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Shut Up Sit Down review scared me off of this one, with it’s talk of the game playing itself once you understand how everything works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can understand that criticism. Combat is a bit repetitive, as it is in most dungeon crawlers. It really depends on how into the exploration and environment you are. If the magic wears off, I can imagine the game becoming a chore. Fortunately that hasn’t happened for me.

LikeLike