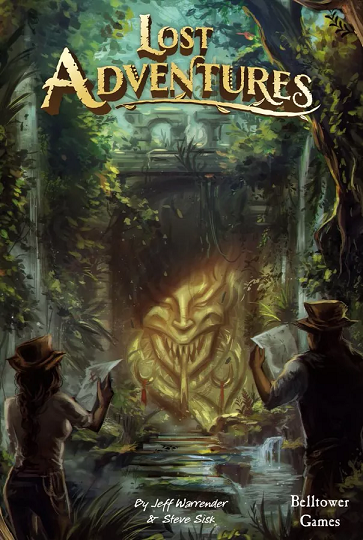

Lost Adventures is every bit the look of a mouse. The box is small and unassuming. The only components of quantity are mini-sized cards and run-of-the-mill black cubes. Your objective is the plainly titled “golden chalice”. Aside from the competing adventurers sitting around the table, your primary antagonist is a faceless black pawn that begins in Berlin (wink, wink). Even the name threatens to fade into darkness and slip out the back door.

All of this sets the stage for flat expectations.

Crack the damn whip. This thing has the bite of a poisoned date.

This style of Indiana Jones pulp adventure game has not previously been tackled with overwhelming success. The Adventurers series from AEG is the most well recognized, a tactical experience where players run through a temple dodging boulders and solving puzzles. It’s a fairly strong release, one that’s joyful and singular, but it also lacks scope and is a bit flimsy. Flying Frog’s Fortune and Glory is closer to what Lost Adventures attempts, but that older title is bloated, repetitive, and really lacks the pace of Raiders of the Lost Ark. It’s Indy in pretense only. Incan Gold and Escape: Curse of the Temple are worthy titles, but both are narrow and don’t capture the grander adventure.

While the bulk of those previous titles can be described as classic Ameritrash board games, Steve Sisk and Jeff Warrender’s Lost Adventures is really an old-school Euro-style design. It sits more comfortably alongside Tikal or Thebes. The setting is there, but it’s in broad strokes and somewhat abstract, coming into sharper focus during the latter half of the game.

But let’s begin with the first half. Roughly 30 minutes of this hour-long expedition is spent traversing a map to visit key locations in Europe and the Middle East. Players are looking to decipher clues, question key individuals, and uncover hidden truths. This really carries Tobago vibes. That 2009 Bruce Allen design had players driving around an island and unraveling the mystery of hidden treasures. You did this by learning clues such as the treasure is on a jungle space, or within a certain distance from a landmark. It was neat and clever, and it’s still a relevant design today.

Lost Adventures is not precisely the same experience, but you do uncover information piece-by-piece, attempting to elucidate important elements such as where the golden chalice is located, what threats you will face in the temple, and which of four chalices is actually the real deal. It’s all prep work for the second portion of the game, the finale where you make your way through the temple and face several challenges before attempting to snatch the one true chalice. It’s very Last Crusade in tone, and it extends meaningfully from that first half of globetrotting.

As I said, much of the setting here is distilled to very simple and direct components. After moving to a location, you flip a card representing a contest or pivotal action scene. While the card bears a descriptor such as “foot race through an alley” or “meeting with an old friend”, it’s easy to overlook the title and just focus on the symbols. The cards, much like Gloomhaven, simulate the rolling of dice and generate a variable number of successes. You spend these points to uncover hidden information, grinning as you make notes on a private sheet. What works wonderfully in this map phase is the subtle degree of interaction.

First, there’s a time limit as this portion of play only lasts five rounds. This places a degree of pressure, as you will never be able to look at all of the necessary cards and fully prepare. You must triage your movement path from a number of suitable options and adapt your plans according to the developing board state.

Some clues you may glean from other players. After taking your turn, you either place a new character card into your tableau or flip an existing card to its stronger side. These represent tools or skills and provide symbols that increase your effectiveness during the map or temple phase. This is a key decision in the game, again, as you’re not afforded enough time to cover all possibilities. So, when you spot Wolfgang viewing a hidden temple challenge and placing a “Fedora” card into play that has several arrow symbols on it, you can make a pretty clean deduction. Not all information is so clearly signaled, so you need to devour what crumbs are dropped.

Another element of interaction is that clues are usually easier to gain once players have seen them. This creates a sensation of following the other protagonists’ trail in a thematic pursuit. This gradual easing of the information barrier pairs well with the not-Nazi pawn threatening to hamper your abilities. Both elements form a nice texture to the adventure phase. The decision on where to travel can be more nuanced than at first glance, as several layers interact with various factors and contain a range of tradeoffs.

Then round five ends and the game stands on its head and starts spitting wooden nickels.

I have a real affinity for designs that offer segmented experiences. Jaws: the Board Game and Arkham Horror: 2nd Edition both radically shift perspective as they focus on the showdown phase. Lost Adventures does this by narrowing the exploits to the final sequence of hazards and eventual reward. The mechanisms are swapped out for an entirely new game, which is delightful and jarring. The clean break mechanically is a wonderful way to provide oomph to the narrative transition, and it frames the final act theatrically.

The temple phase is more direct and competitive with an edge. Players face several challenges in unison, bidding against each other and the neutral adversary. This is the cleverest quality of the design, as your bid is paid in the resource hubris. This is your defiance and pride, facing down the temple and its supernatural forces in order to claim the chalice. Your knowledge mitigates the cost, but you need to push yourself just above your competitors to move farther along the track and arrive at the chalice room first.

The issue is that everything comes to a head in the final scene where you test to see if you can purge your hubris. If you’ve pushed too hard and acted too recklessly, you will fail. The naked flesh of your face will melt, reducing your adventurer to a husk of a being that can only be identified with dental records. But if you push too slowly, you will not arrive in time to claim the chalice.

This is a magnificent sequence. Like the rest of the game, it’s a relatively simple mechanical framework, but this portion provides hefty tension and demands thoughtful strategic focus. It’s also a significant injection of drama and an escalation in turmoil as you wince with each bid and brace for impact.

Hubris is the thematic focus of the design and where the larger subject matter emerges. It’s always the temptation, offering additional successes when performing tests in the map phase. Of course, it’s hard to say no when the pain is delayed, like a nasty credit card bill off on the horizon.

The way this mechanism gives form and reflection to this behavior is excellent. It reinforces the genre themes and actually elicits insolence from the players. It’s the defining quality of Lost Adventures as it interweaves theme with player action in a stellar yet simple way.

There is just something about this meek little game that has retained my attention. It’s soulful and does a great deal to modernize the German-style Euro of old, pairing sound mechanisms with a more modern artistic approach of capturing theme. A common criticism will be the somewhat abstract setting. We’ve come to conflate theme and setting when discussing board games, and many will decry this design’s lack of flavor text or prescribed narrative moments. It’s also a small experience as I’ve stated, and some may want more from an iconic pulp adventure design.

I think a more legitimate criticism is that the game does not cede even more ground to its malleable visage. For instance, why the “golden chalice”? Or why is the enemy faction a member of a society with the obnoxious acronym SPADE? This penchant for supplying unneeded minor details is also seen with in-setting character name suggestions if you’re struggling on the creative front.

All of these small elements of world-building feel a little out of place. I’ve come to compare this game to Jenna Felli’s Shadows of Malice, an underrated indie adventure title. That design is very broad in its narrative strokes, randomly generating monsters of randomized traits for you to fight. It’s a somewhat avant-garde design, eschewing genre norms and presenting its own identity. Lost Adventures hovers in a similar space, providing just enough of a framework for players to fill in their own details and narrative. That works splendidly here, as it has such strong source material that vivid scenes arise with little effort. This title is also less esoteric and a little more grounded in the hobby’s history.

While Lost Adventures is somewhat flexible, I don’t find it particularly effective with just two-players. Four adventurers are ideal as there is more depth to the maneuvering and especially the hubris challenge. Three is serviceable as the bulk of the experience is intact and playtime can be a swift 40 minutes, positioning it as a meaty filler of sorts.

It’s also somewhat of an awkward game to wrap your head around initially, particularly the bidding. Once you understand it conceptually the process is a breeze, but new players often take a moment and a couple of examples to internalize the system. Even then, you will likely need to remind them how it works prior to the phase switchover. Yet, it is a streamlined and simple ruleset on the whole. It’s the type of game you can come back to months later and remember how it all fits together and hums along.

Throw it on the table and it just delivers. John Williams tickles the back of my mind as players feign shrieks while dramatizing their face sliding off their skull. And as the journey unfolds, Lost Adventures is an impressive game that is small only in the physical sense. Of course, it’s not going to have the cultural impact of Indiana Jones, but that hasn’t stopped it from leaving a mark on me.

A review copy of the game was provided by the publisher.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my efforts, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.