This is Prospero Hall realizing their full potential. Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Slaughterhouse is better than the previous echelon of Jaws, Rear Window, and Horrified. It’s the studio coming together to produce a relatively accessible mainstream board game with engrossing, clever, and intense design finishes. This is white hot and blood red.

As an adaptation of the classic Texas Chainsaw Massacre film, Slaughterhouse is full of seething soul. The first thing it gets right is a real sense of dread. The terror doesn’t unfurl all at once.

One player takes on the role of the Sawyer family. They start off a disturbing obstacle, controlling only the “Old Man” who wanders the family’s house. His activity vacillates between sweet talking nearby characters – effectively building currency for the antagonist player to spend on later abilities – and delivering stray blows with his blunt weapon.

The rest of the players are the trespassers. They’re lost souls who have stumbled upon the property and are looking for a way out. Or to burn the damn place down. Or to escape with some belongings. This depends on the selected scenario. Of course, they’re all killer.

So, these unnamed trespassers are scrounging around, digging through the paraphernalia of psychopaths in search of something useful. You can’t harm the villains. Even if you dig up a bone shard or find an axe, the best you can do is maim them and slow the brutes down. They are relentless, and they will tear your flesh from the bone and fashion your remains into a new love seat.

But you’re in a hurry. The longer you wait, the more terror builds as new Sawyer’s emerge from their holes. After the Old Man, we see the “Hitchiker”. He’s an unhinged murderer that stalks out of the woods and can climb through the house’s windows. He wields a switchblade and will not hesitate to carve you up.

Dilly long enough and the big show, “Leatherface” arrives. This is the beast of a man who wears another’s face as a mask and wields a chainsaw. He will absolutely destroy anyone caught within his vicinity. You better run.

That’s the cadence of play. Trespassers bolting around, searching spaces for items like car keys, fuel, and the occasional weapon. But every inch of that house bears a shadow full of creativity. Every small mechanism and detail a nail in the greater structure’s menace.

Take Trespasser movement. You can choose to spend your precious actions walking to progress through the house slowly but quietly, or you can run for greater efficiency at the cost of additional noise. Moving through doors causes noise too, as does searching. Plowing headlong through the rubbish is ill advised. At the end of your turn you roll the dice – two bone colored uglies – and bleed off as many noise tokens as successes. The rest get converted to terror and awarded to the Sawyer player. You’re gifting them the tacks they will drive into your fingernails.

The terror being spent to bring additional antagonists into play is ingenious. It creates an escalating tension that begins a quiet violence and builds to revving carnage. You can feel the stability of the environment crumbling away, control slipping through the sieve along with bits of your existence. It’s a splendid arc.

Another aspect is the board. The design is a marvel. The main section depicts the first floor of the Sawyer house and an outside perimeter of 20 yards or so. The interior is a maze, with rooms oddly situated and joined by noisy doorways. These lead you through the labyrinthine interior as if you’re wandering the husk of a fallen demon. At times, you will actually feel lost, trying to figure out the quickest way outside or to a particular location.

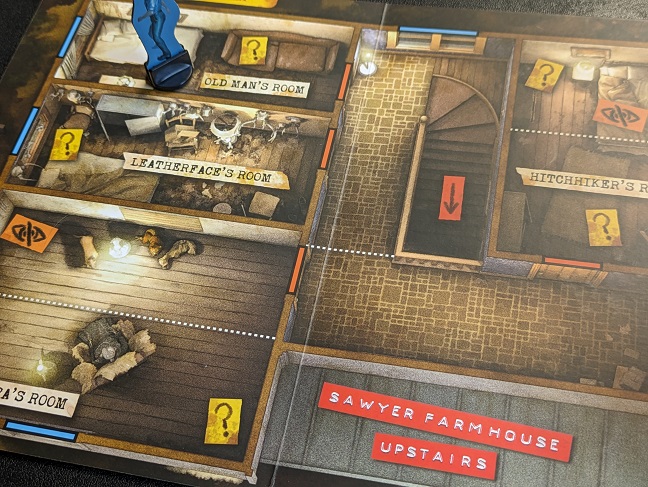

You can wander upstairs. This is a separate smaller board situated nearby. You will likely need to head there at some point to snag a gasoline can or the keys to the rusted van sitting outside. But there’s only one way up or down, a chokepoint which looms oppressively. As you creep deeper into the bowels it feels as though you’re descending into hell and will never make it out alive. The locale is also enhanced through Horror tokens the Sawyer player seeds the game with at the start. These are flipped as you enter their spaces, revealing one-time events or ongoing effects. They’re all a doozy and hasten the bloodshed. It seems as though the environment itself is out to get you, warped by this twisted family and intent on your death. Surviving at all feels a cheat, as if fate lost out.

The brilliant details just keep coming. The smallest of touches, such as the Sawyer characters all represented as miniatures and the Trespassers as standees, hint towards a greater theme. In this instance, the authorial intent is clear that the perceived protagonists are not the central figures of this story. The Sawyers are the main characters, these individuals spotlighted and centralized in the greater motif.

Damage is another wonder. Each time a Trespasser is wounded, the attacker draws one or more cards from the injury deck. One card sticks, representing a debilitating injury with an ongoing effect. Maybe your broken foot means you can’t run anymore, or your traumatic brain injury results in increased future damage. They all sting and leave you disgusted.

There is no health track. Instead, once you’ve received an injury card for each of four categories – brain, heart, foot, and hand – you perish. This is intensely clever. Not only does it manifest more distinct narrative bloodshed, but it also makes it more difficult to finish off a character. A fresh Trespasser can have any of the four categories applied, but one on death’s door needs a specific type of card inflicted. It’s a soft touch to extend life in a game that happily embraces player elimination. And it’s such a fantastic way to do it. Texas Chainsaw Massacre without grisly death and actual loss would have been a wolf defanged. Not this bastard. It will dig its teeth in and separate your soft tissue.

All of these details arrive with fury. Over the course of 30 minutes, each system and flourish send a jolt of electricity up the spine. It’s an album where the hits keep coming and never stop.

The title track is undoubtedly the legacy mechanism. It appears a small detail, but it’s my favorite riff in this composition. You see, each Trespasser starts off with a personal item. These are special pieces of gear that are more than they appear. They are stand-ins for variable player powers, offering a degree of characterization in the form of an item instead of the typical asymmetrical starting ability.

This is important.

What this does is detach the character boards and standees from specificity. By this, I mean that instead of recreating the original Texas Chainsaw Film, it has the players slipping into unnamed roles. Perhaps these represent yourselves or another character you can manifest in the mind. Either way, they’re not named. So instead of a special power you see repeatedly across multiple plays, they have a personal item selected from a larger set of options.

Now, by divorcing these characters from specific identities, it forms the basis for the game’s metafictional continuity. Each play is a new set of Trespassers lost, stumbling upon the location which has seen countless horror. If you recall from the film, the Sawyer house is full of bones and previous victims. There’s a continuum of violence that extends across time. Each play, is set in the same metafiction of your table. At some point in the future, after that previous set of characters was eviscerated.

I just see Rust Cohle sitting at a table, surrounded by empty beer cans, and mumbling about time being a circle.

This isn’t a small detail in terms of impact. It’s reinforced in a couple of ways. When you die and are left behind, your personal item is then stored with the regular item deck. In a subsequent play, you can discover this item while searching and utilize it. Not only is it a substantial boost in a moment of need, but it’s a pointer bringing attention and reflection to that previous play. The table stops, perhaps smiling or scowling, remembering that time a few weeks ago when Aaron’s Trespasser was gutted and left still on the dirt path outside. Now you’ve found his jacket, your fingers running across the dried blood on the inside of the sleeve as you slip it on.

There’s almost no effort to implement this brilliant system. No overhead or maintenance. You just take that special item card and put it into the main deck. As this item defines the character, it forms a representation of their identity and their body. It’s the equivalent of their bones left behind, stacked amid all of the other’s lost in this hellscape.

The second quality supporting the legacy system is the inclusion of achievements. This small set of goals is spread across the game’s five scenarios. They form background objectives to shoot for, perhaps tempting hubris in order to achieve glory. For example, the first scenario has the Trespassers searching for items in order to escape in a vehicle. While not a trivial task in its own right, if you can manage to find the necessary parts to escape in two separate cars then you hit an achievement.

The beauty here is in the incentive. If you manage to accomplish one of these meta-goals, you unlock a new card or two. These are permanently shuffled into the game’s decks. It’s not a big deal in terms of new content. This isn’t Pandemic Legacy. But it’s the smallest of touches that helps support the idea of the game’s sense of continuity.

There’s just so much to find pleasure in. Look, one of the most important elements of this release is in how it combats the Prospero Hall problem. This is a particular criticism I’ve had with much of their design-work. They take a hobby mechanism and translate it to an intellectual property with a light ruleset for mass consumption. It’s typically a pleasant enough package and the game holds up better than what we used to think of mainstream board games. But there’s rarely longevity for a hobbyist. They struggle on that thin line of appealing to a broader group of people and those who play games regularly.

Jaws manages to overcome this limitation by offering depth through competitive hide-and-seek which proves much more expansive and limitless in comparison to a regulated AI opponent in a light cooperative game. It also offers a truly exciting climax. Rear Window includes a mechanism to inspire paranoia and capture the film’s central theme. Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Slaughterhouse is the best of the lot. It utilizes challenge as a foundation for dread. It offers a rich setting born out of the seminal film, as well as the game’s meta-narrative. It captures tension like few others, lining up besides gems like Psycho Raiders and Nyctophobia. It’s a much larger game than the small box and small cost.

I can’t get enough of this. It takes the tradition of an oldie like Last Night on Earth and modernizes the broad structure with genuine sparks of imagination and originality. It’s a near perfect accomplishment of adaptation, never pulling a punch while still riding the line of mainstream accessibility. I can muster up some criticisms, such as sessions with a low player count occasionally resulting in Leatherface never appearing, or variance infrequently leading to an easy playthrough lacking tension, but these are minor notes across the extent of the game’s impression.

This is adaptation at its peak. It’s the promise of Prospero Hall fulfilled. This is the consummate achievement even the most skilled of designers rarely achieves. Bravo.

A review copy of the game was provided by the publisher.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my efforts, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.

2 comments for “Peak Adaptation – A Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Slaughterhouse Review”