‘Expected’. This is the word that continually flitters across my mind when I’m thinking about Apiary. It’s a very conventional Stonemaier Games title. It integrates the trend of a nature setting (bees) with a slight twist of a popular but divergent genre (science fiction). It’s an interesting concept that will raise your eyebrows upon first contact, but the actual implementation isn’t dangerous or wild. It’s exceptionally comfortable. Cute bees head to the stars and allow for worker placement, spatial tile laying, and the crafting of occasionally explosive combos. Comfortable is Stonemaier’s brand, and Apiary provides that feeling immeasurably.

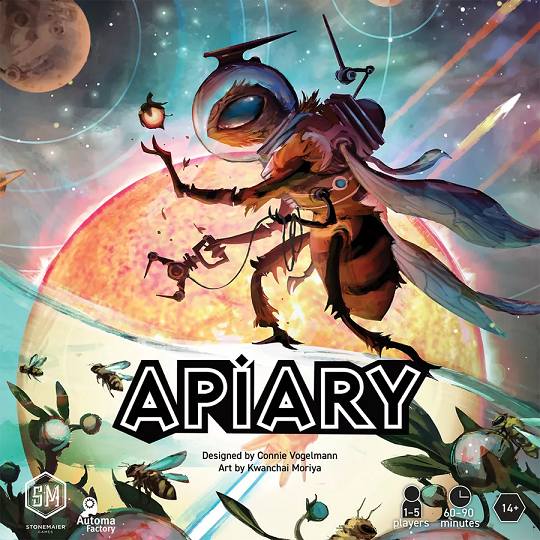

One of the real strengths of this publisher’s oeuvre is in widespread appeal. The nature setting works because it’s visually attractive and doesn’t fall into the over-worked categories of conflict or trading. But the sci-fi pairing helps it pop a bit in comparison to the increasingly bland titling and settings of the nature genre. Who is going to hate on space bees? Especially when you execute on the concept with such lovely pieces and graphic design.

Similar to the game’s setting, the core loop is familiar with a gentle quirk. As your workers get bumped from their positions on the board, they age and increase in strength. This variable worker implementation nods towards Jamey Stegmaier’s Euphoria, although I find the mechanism here much more satisfying. That is primarily due to the retirement system.

As your worker bees reach their peak level, they will then fade into oblivion once bumped from the board. Don’t worry kids, they’re just retiring to a dirt farm back home. But you, master of bees orchestrating your colony in the shadow of the cosmos, you get to place the little bugger on a scoring spot and receive a reward.

This is the motif behind Apiary. Entropy gives way to beauty. As your colony grows and dies, the ecosystem blossoms in earnings potential. You churn workers searching for specific tiles to place on your personal board – a la Castles of Burgundy – and ultimately seek to break the game by securing massive point swings through objectives carved out during play. It manages to approach a sense of wild in the late late game, occasionally allowing you to unearth a seed card that offers a ridiculous number of points. But it never quite tips over into Glory to Rome territory and become truly unhinged.

The bee-service is established through appropriate titles for the various sub-sections of the game, in addition to adopting a hexagonal aesthetic. Most of this is very wispy, never really solidifying into any measurable sense of setting. But it’s serviceable enough. It conveys a general tone and grounds the systems in something purposeful.

There is one particular aspect that I do find intriguing on a deeper level. The style of worker placement here has a satisfying cadence. It goes with Luke Laurie’s Manhattan Project approach where players must spend their turn pulling back workers. There is an interesting tradeoff due to the bumping of spots. As workers return to your pool you may immediately ready them for a future turn or you can stash them in a state of slumber and wait until you’re ready to pull the rest of your bees off the board. This allows you to utilize displaced bees for additional benefits, working your farm tiles and producing extra resources.

But what’s gripping here is the tempo. Quickly, players start getting into their own rhythm that’s syncopated with that of the others. You’re not all stuck in a similar loop, as some will want to retrieve their bees early. Even your total number of workers will be irregular soon enough. So, it’s all sort of off-kilter with each player moving to their own time signature.

In the jumble of placing and recalling which births that mix of tempo, it feels as though the play surface is jittering and alive. It conveys this sensation of a bee colony, frenzied in poetic labor. This wouldn’t be instilled if designer Connie Volgemann opted for a more traditional round structure of placing and retrieving workers. This quality is the most pointed and unusual aspect of Apiary, and it’s the area where it most manages to separate itself from the rest of the field.

The rest of the design is, well, expected. We’ve seen point combo-ing like this before. You attain end-game scoring tiles and cards, dig through market rows looking for engine synergy, and try to leverage the way your colony has developed with a matrix of victory point options as they arise. This is another one of the generous Euro-style designs that is becoming popular. Resources aren’t extraordinarily tight, and you are afforded growth continually. It feels most satisfying when you uncover one of the stronger scoring combinations – sometimes by sheer luck of market availability – and explode past the expected ceiling. In these moments, Apiary feels great and leaves you with a smile.

As is becoming a signature of the publisher, the game leans into asymmetry as a source of flavor. It cribs from Scythe by combining two separate asymmetric variables in the form of a faction ability as well as a colony board. One earned criticism of this studio is in the lack of balance with certain factions or groupings. To their credit, they playtest an incredible amount and are always intent on iteration and tweaking strength.

I have not encountered this quality yet with Apiary. However, I can’t help but note that this trouble is arising as a result of Stonemaier’s desire of strong asymmetry in combination with low-conflict efficiency games. The bulk of highly asymmetrical experiences in the hobby are area control or skirmish designs. They allow players to police themselves, self-correcting for emergent leaders and utilizing negotiation as an organic aspect of competitive play. It masks slight problems and avoids mass criticism.

With this style of game – also, see Tapestry – there is no mechanism to reign players in. Like virtually all low-conflict designs, it’s about raw efficiency and utilizing your actions better than the bum sitting next to you. Assuming everyone is playing competently, it could be compared to pushing two boulders down an enormous hill. If one is even fractionally quicker, it will have gained substantial separation by the time it reaches the base of the mount. In pairing two separate asymmetrical abilities, this game makes its own life difficult by increasing the wide range of power combinations. I’d be surprised if it was perfectly balanced, and the structure of low conflict means it’s more likely to eventually come out.

This hits on many things asserted by modern design principles. Attention is maintained between turns, the pace is snappy, and resources are plentiful not rare. While it’s certainly possible for play to drag with a contemplative player-set, an experienced group can breeze through this one in 80 minutes or so. One could say it flies. Because it embodies so many of these standards and the setting is so agreeable, it’s easy to see this as the crowd pleaser.

Apiary is pleasant. It doesn’t seek to jostle or throw you off balance. It’s not interested in something grander. It offers satisfying point-engine construction through a clever worker placement loop, and it does so with clarity and editorial proficiency. Like the majority of the Stonemaier catalog, it sets a clear and attainable goal and it follows through on its promise.

A review copy of the game was provided by the publisher.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my efforts, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.

As always, great review!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Yes, almost every Stonemaier Games I have played is a B+, but with a good theme, great presentation and component quality, and a decent rulebook.

The games I prefer are more unique and innovative, but I have found that the trade off is that many of these games are hard to teach and can be very fragile (inis, infamous traffic, John company, art of of the evangelists, great Zimbabwe, ….)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, very good point. Those more quirky designs can be difficult to effectively introduce and can result in awful experiences with the wrong people.

LikeLike