There is no “you”.

You don’t exist.

It seems as though we have an autonomous identity within. We feel as though we are a central being that is inhabiting our bodies. From this focal point we exist in a state of selfhood, an experiencer of experience. We can reflect on our past, present, and future and recognize our self as a constant.

This sensation is an illusion.

The experience of an “I” is a construction of various processes. This “I” does not exist independently of the experience itself. Our consciousness interfaces with the world through a multitude of perceptions that are integrated into a cohesive narrative. The continuity of experience is what creates a sense of identity.

This is “the illusion of the self”, as originally theorized by the 18th century philosopher David Hume. It is also a foundational tenet in Buddhism, which professes that we are all part of a greater whole and the self is a major cause for our suffering. It’s referenced in non-dualism, various meditation practices, and by countless modern philosophers such as Sam Harris.

In addition to board games, I spend a lot of time thinking about philosophical topics such as the self-illusion. Sometimes I think about both.

Let me explain.

There is a common thought in this hobby that gameplay is the primary consideration of a design. “It’s the gameplay that matters” is a refrain I’ve heard many times. Not to pick on anyone in particular, but this line of thought is most commonly seen when discussing publishers that espouse a simple aesthetic while minimizing production values. Splotter comes to mind. Winsome Games too.

But this mantra is uttered by a large sect of gamers. The meaning is clear – that rules and systems supersede components and visuals. I certainly understand where this line of thought comes from and why someone would hold this position. It’s a reasonable view. I believe it also manifests as pushback on the swathe of overproduced products continually spewed from the womb of crowdfunding.

Framing the gameplay this way alludes to a distinct identity. It’s positioned as a sovereign entity that lies at the heart of the product itself, something you could extricate and utilize elsewhere. This, again, seems reasonable. We can point to games being “rethemed” such as Alexander Pfister’s Mombasa reappearing as Skymines, or Gale Force Nine’s Sons of Anarchy: Men of Mayhem becoming Wise Guys.

In isolating the focal point of these games to the intangible collection of systems, we are effectively identifying a “self” at the center of the experience. Gameplay is elevated to a heightened status, relegating tactile and aesthetic elements to ancillary roles.

From a certain angle this aligns with reason. Just as we wouldn’t think of our appendix as identical to our self, we also wouldn’t think of Sons of Anarchy’s small cardboard money stacks as indistinguishable from – or perhaps commensurate to – gameplay.

Except, I think this is a diminished and mistaken way of viewing what occurs during play. Gameplay does not exist as a spirit at the center of the thing.

We are on firmer ground if we view games as a facilitator of experience. The gameplay is integral to this process, but it’s unmerited to divide all of the aspects that constitute the whole. What the gameplay does is work in tandem with components and artwork. They are all fundamental to the experience.

You can’t extricate this spirit from experience itself. The pieces you touch and look at are part of the magic of play. This affects how we interact and perceive the game. When you modify any aspect of the whole, the experience changes. It’s something different.

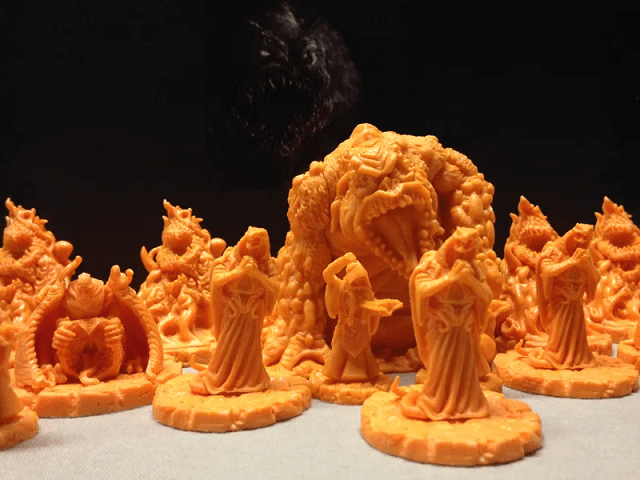

This is most obvious when looking at games at the far end of the spectrum. Take Cthulhu Wars. We can imagine a game that removes the obscene statue-like miniatures and replaces them with flat cardboard chits. We can imagine the map being black and white pieces of paper taped together. With gameplay remaining intact, the experience of play would be entirely different. I’ve seen players rush towards getting their Elder God into play, not for strategic reasons, but because they wanted the visceral intonation associated with placing this huge miniature on the board.

Cthulhu Wars: Duel, as well as “rethemed” titles, show that you can remove the ruleset from a game and re-use it elsewhere. But you’re not transferring the spirit of the game. I’ve used the figures from Cthulhu Wars in the miniatures game The Doomed. My experience of playing Cthulhu Wars certainly leaves a sort of mark that hangs at the edge of thought whenever I see these enormous miniatures, regardless of the game I use them in. They’re not the soul of the game either.

While there is a certain intuition that transferring my brain to another body would retain my “self”, this is not reality. The physical processes of the brain and how we interact and utilize our bodies are integrated strongly with consciousness. This is the same for board games and their contents.

“But, what if I don’t care about components?”

That’s a fair attitude and certainly a portion of the hobby. This stance, however, is immaterial to my claim. Just as someone may not care about a particular decision regarding gameplay – such as being ambivalent towards variable player powers or lacking preference on area majority versus area control – this doesn’t change the fact that all of the elements of a game are subsumed in experience.

It’s also important to understand that this essay is not veiled miniature proselytism. The notion that gameplay is not sacred and autonomous holds true for all artistic visions. Cave Evil, for instance, is not a lesser experience due to a lack of miniatures. The lo-fi production values and black and white presentation are purposeful. Those qualities are integral to the intended experience and changing them in any aspect alters Cave Evil itself.

Maybe you’re skimming along and reacting with, “well, obviously.” I don’t think any of this is too controversial. But if you pay attention to popular discourse around games at both extremes of the production spectrum, you will see this discussion creep to the forefront. The recent deluxe edition of Food Chain Magnate was full of this attitude. And yet, if you examine the experience of play closely, it’s obvious that it is fundamentally changed with enhanced components. If it wasn’t, people wouldn’t be paying so much money for these types of dressed-up revitalizations. People wouldn’t be substituting plastic for cardboard in Quacks of Quedlinburg. People wouldn’t be addicted to metal coins.

The soul of a board game is not the gameplay. There is no “self” here, there is only experience. It’s not just the gameplay that matters. It all matters.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my efforts, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.

Great article! And very true. I definitely used to think of myself as an “only the gameplay matters” but after going through the full process of publishing a game, playing hundreds of other designers prototypes, and, eventually finding a friend who prioritizes neoprene mats, metal coins/iron clays, and buys everything Chip Theory Games makes, I have been swayed to believe k was missing an important piece.

As you said, gameplay is obviously important, but you’re ultimately building an experience. An activity that people will bring out and show to their friends and family. It needs to be something that shines in every regard, can be understood by wide range of people, and can be enjoyable when played over and over again.

Honestly what we expect from publishers and designers time and time again is nothing short of miracles and yet they often deliver (even though many still have complaints after the fact).

It is an amazing time in history to be a board gamer. There truly is a smorgasbord of great games available (which is why most gamers have100+ games on their shelves).

Thanks for the great article!

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and commenting! I’m glad it resonated with you.

LikeLike

I very much appreciate you looking at games through a more serious, explicitly philosophical lens in this article. I very much disagree, both with Hume in general and with your particular thesis here, but don’t get me wrong: I enjoyed it a lot, and it takes someone writing something I don’t agree with to even get me to think about what I myself think. Thanks Charlie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I’m glad I was able to inspire some introspection, and I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

LikeLike

One of my favourite blogs on boardgaming. Thank you for this thinkpiece!

I always greatly appreciated quality components, and what they bring to the table (even “simple” but superb 2D graphics in card games such as Arkham Horror LCG), although I also abhor the overproduced Kickstarter trend – not just because I cannot with good spirits spend so much on a game, but also because it prevents good story-oriented games to reach retail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, that’s very kind of you to say.

I also am disappointed when the large overproduced games remain Kickstarter exclusive and are deemed not viable at retail. It’s a worrisome trend.

LikeLike

really nice article.

I once was one of those people who only cared about ‘gameplay’, but I have since come to the realization that everything matters. Theme, setting, components, rulebook, player aids, artwork, the teach…. all play a role in success of the process of playing a board game with others.

Yet, in my current framework does slightly prioritize gameplay.

my current framework to evaluate games are based on three questions. First, ‘how close is this game is to the platonic ideal of this type of game?’ Second, ‘How likely is this game to be someone’s favorite game?’ And third, ‘Is there an innovation or unique contribution in the game?’

my favorite question is the second one, as a game that could be someone’s favorite must be exceptional in one area, or exceptional when taken together.

So as an example, the opinionated gamers ran an article on 20 most underappreciated games, very good article, but one game, La Citta, had two gold medals, but only those two gold medals, so ended up 15th. Under my framework, because it’s a game that was multiple people’s favorite, it would have featured much higher. It does have huge rough edges in that it can be long, and production is not pretty, but it has really interesting emergent gameplay and mean player interaction.

So in general, this framework will support divisive games that tell a story or are unique, even games that I don’t like. Splotter does very well under this framework, even though I hopefully will never play food chain magnate again. And even though I think just about every Jamey Stegmaier/Stonemaier game is a B+A-, the huge commercial and critical success of scythe, viticulture, and wingspan cannot be ignored. These games cannot be dismissed as only being ‘pretty’. They also have a good marriage of theme and components, streamlined to having a medium complexity, and have good rulebooks. These things matter.

some other games that rank very, very highly on my metrics: TI4, Inis, Millennium Blades, Mysterium, Codenames, Mage Knight, Guards of Atlantis, Sidereal Confluence, Shobu, ….

LikeLike

Very interesting.

I would absolutely agree that not all aspects of a game should be valued equally. Gameplay is certainly more important than aesthetics.

Your methodology is robust. I like it. It’s given me something to think about. Thank you.

LikeLike

I often say that what we call games are really just decorations. All those boxes on the shelf? Those are not games. They are very pricey thick posters holding plastic, wood, and cardboard trinkets inside. But this is not me dismissing components. The rules aren’t games either. Mistaking them for games leads to BGGs obsession with mechanisms as if they mean something. No. Games only exist when we play them. They are, as you say, an experience. Now some combinations of materials and rules produce an experience we enjoy and some don’t. And I think most people will find some enjoyable games have lots of material and others don’t. And unenjoyable games will feature both as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said.

LikeLiked by 1 person