I was nervous. I shouldn’t have been. I should have trusted Wehrlegig.

Jo Kelly and Cole Wehrle’s Molly House is something different. It’s a historical game about 18th century British Mollies; a topic I knew nothing about. These gender-defying non-conformists met in private to celebrate their lifestyle and escape the persecution of society. They lived a life of secrecy and fear, but also one punctuated by moments of jubilation and honesty.

Wehrle’s John Company Second Edition is one of my favorite games. It’s also an experience that I find enveloping, as it turns me into a right bastard ready to set the world afire if it results in my own prosperity. I was nervous that Molly House would elicit a similar sense of involvement.

Look, I’ve written and re-written this paragraph multiple times. I was going to list my bona fides, but it all feels disingenuous. Despite my political leanings and support of the queer community, I would be lying if I pretended to be comfortable with the idea of immersing myself into the role of a person from such a culture and sexual orientation. There was certainly trepidation on my behalf.

This worry was unfounded. My fear did not belong. Molly House is, above all else, a game of friendship, celebration, and joy. Occasionally, it’s also a game of betrayal and persecution.

You might get what you’re after

Approaching Molly House for the first time is an interesting experience. It has a classic appearance emblematic of the Wehrlegig brand. Undeniably, it’s a gorgeous thing. The board and pieces possess traditional form, with the layout of spaces hewing most closely to Monopoly of all things. The outer rim consists of large areas and players take turns rolling dice to move along the path. Of course, this game shares virtually no actual kinship with the Parker Brothers staple, but its shape certainly bears a surface level resemblance.

Like much of the abundant symbolism in this game, I find this connection consuming. Molly House is about non-traditional behavior burgeoning in backrooms and alleys. The physical form parallels this lifestyle, with the accustomed Monopoly appearance masking a very unconventional system. This congruence of theme is fascinating.

Fortunately, the singularity of this design is near immediate. It mixes a liberal roll and move mechanism with a winding card system that feels foreign and difficult to conceptualize. Let’s see if I can pass it along into your noggin.

Cards consist of one of four suits and typically display a numeric value. Each suit maps to one of the important Molly Houses on the board, which limits the cards applicability in certain actions. A subset of the deck holds no number and are instead face cards with their own special applications. Another subdivision of these face cards includes threats – obstacles such as rogue characters that are unpredictable in behavior, as well as constables representing the antagonistic entity the Society of the Reformation of Manners.

This organization is the primary threat of the game, adding a dimension beyond a simple competitive victory point race. The members of this group pursue the goal of improving public morality through suppressing vices and promoting piety. They’re a rigid folk that would like to imprison or put you to death. You know, good people. You must balance avoiding their gaze while committing to a lifestyle of splendor. Ultimately this game is about trying to attain happiness with a devil as your shadow.

Wait ’til the party’s over

Let’s get back to those cards. They are acquired partially through a small market reminiscent of the Pax series of games, albeit in a very stripped-down manner. There are only four faceup options available, and to select one from this row you must perform an action at a specific space that maps to the suit of the card you’d like to yank. You always have the ability to lift a card from the top of the deck instead, however.

The cards of Molly House are its main tool of expression. They’re a codification of actors and actions, used in various ways to conduct song and dance in a conjoined effort of celebration. They’re the instrument by which you author thoughts, feelings, and human experience. These beautiful flashes happen in the defining moments of play, which are Festivities.

The structure of the game is simple: agents move and perform a single action on their turn. The action selection depends upon the space a player currently occupies as well as what cards they have in their hand. There are two distinct halves to consider. The first is managing cards and how they flow from hand to reputation and gossip. The second is utilizing these cards to participate and drive Festivities.

Festivities are where Molly House grows obtuse. It’s the opaquest portion of play, and it’s also the most significant. Abstractly, I’m fond of comparing this resolution system broadly to the structure of Texas Hold’em, or rather, cooperative Texas Hold’em. The deck contributes a flop of a single card, then players take turns placing one of their own cards to the table. This process repeats a second time.

Commonly, the goal is to build a set of cards among the group. The clouded opacity exists because there are several different types of sets to build. The strongest is a straight of all the same suit. Next are three cards of equal value, but they must be accompanied by a Queen. Third is a Jack as well as a straight of any combination of suits. Finally, if none of those can be constructed, the four lowest cards are chosen and instead of a raucous celebration of love, a quiet gathering occurs with restrained pleasantries.

This hierarchy of various goals, the awards associated with each, and the hitch that are Rogues and Constables really jam up the mental gears of new players. Molly House is a difficult game to internalize, and it’s almost entirely because Festivities are oblique and without common touchpoints we see in other designs. This complexity fades once players come to grip with the system and understand how cards flow from point to point, but it’s a rough game to drop into.

Once players are able to pluck out and touch the more subtle nuances, Festivities grow exceedingly more interesting. The back-and-forth card play becomes a negotiation. People start asking the group what kind of sets can be constructed. Promises are made and momentary glimpses of flirtation and intimacy produce indulgence. The cooperative and creative use of cards often feels like a party mid-motion. A dance is occurring, with players enacting various movements as they flow with the rhythm. There’s an entrancing artistic human experience conveyed with a clever integration of mechanism and theme. It’s the brilliance of Molly House.

Is out of the ordinary

Sometimes things turn nasty. A promise is made; a promise is broken. You expect a six to be played and instead a two is produced. Rejection is real and the emotion involved is damning.

Each player wants their cards chosen. This participation in the gathering results in the attainment of Joy, which is the wonderfully descriptive term for victory points. You are in search of happiness, and you find it by lowering the disguise of everyday life and giving oneself to the revelry. This is a game of participation, but to get involved, sometimes you need to edge out another Molly. You need to become the celebration.

The sense of exclusion and the division of Joy amongst players can lead to a sense of resentment. This can be exploited by the Society of the Reformation of Manners. It’s a strong counter-element of the design that can lead to unique emergent narratives and absolutely tragic drama.

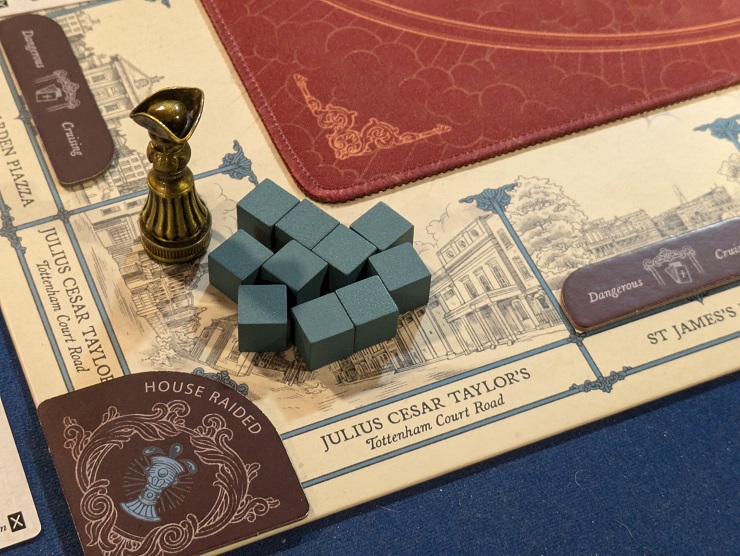

These seeds of doubt begin with hearsay and scandal. As cards work their way through the various nooks of play, they will often end up in the Gossip pile. This is a face-down discard that contains all of the whispers and buzz travelling from loose lips to pointed ears. At the end of each round, a random third of the Gossip are removed while the remaining two-thirds are revealed. Depending on the card mixture, this can result in evidence being placed at the various molly houses. This evidence remains on the board as an existential threat. Eventually enough is accumulated and the safehouse is turned upside down, raided by constables.

In addition to the molly house being permanently shuttered, players who have acquired reputation with that location are doubly punished. Those with the most prestige receive indictments. These cards are dealt randomly from a larger deck and heavily reduce Joy at the end of the game. The most severe may even force a die roll with a possible result of your molly being hanged for buggery. Indeed, players heavily invested in raided houses may find themselves eliminated from scoring on the turn of a die. This is the cruelest of fates. It’s also one of my favorite mechanisms.

Don’t wannna hurt nobody

Beyond avoiding sticking one’s neck out, there is another way to avoid indictment. When sufficiently pressed, you may turn on the Society and betray your people. This is such a cruel fate as pressure builds, and would-be tyrants strongarm you into the role of informer. The mechanical process by which this occurs is an entire thing. There are multiple steps and considerations and it’s all beyond the scope of this review. Unlike many games of this ilk, however, you cannot enter play with the mindset of becoming a turncoat. It’s more of a situational occurrence. It’s a conflagration of game events where you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. When this occurs and you have the opportunity to turn Judas, the decision is heavy.

And this is the final igniting agent that ushers the game towards conclusion. The last element of complexity, and one of the most crucial aspects to understand, is the end game framework of Molly House. Chief among the three end conditions is a celebration with community survival, in which case the player with the most Joy is the winner. This is what we strive for by default and what is most likely to occur with experienced play. A second possible outcome is community infiltration, with the end trigger arriving as a result of all four houses being raided, or a single house accumulating enough evidence to raid it twice. In this condition, only those players who have betrayed their people are eligible to win. Their score is unique, eschewing Joy and instead looking to see how much damage they’ve done to those around the table. It’s a brutish conclusion to an emotional game, and this is underscored by the rulebook’s assertion that it’s uncouth to count your score on the Joy track. The final conclusion is to simply run out of time at the end of the fifth round. This is the worst case, as everyone loses. I have yet to see this happen.

This is a hard-hitting experience. It’s a relatively brief affair, clocking in at two hours for those with familiarity. It’s perhaps the least rules dense of the Wehrlegig gameography, but it feels just as awkward and impenetrable as John Company at first blush. This is not something to approach timidly, although it is one that desires a long-term relationship. The systems will begin to make perfect sense over time. Strategy emerges and discussion becomes more colorful and intricate. Festivities grow to become these focal points of intrigue where glimpses of drama, tenderness, and passion shimmer along the surface of play. It’s an affecting game.

One of the most glaring qualities is that the singularity of the system produces a sense of timelessness. This is exactly the Wehrlegig hallmark. Their suite of games could never be described as “worker placement with…” or “area control but…” They are not of a particular time or fad. They are distinct and unusual artifacts. Because of this aesthetic, it’s impossible to mimic their exploits, as the mechanisms are entirely devoted to motif.

We’re in for nasty weather

There has got to be a way

Burning down the house

The historical setting is a considerable boon for this game’s subject matter. By displacing the various themes and locating the events in 18th century London, it establishes distance through a layer of abstraction. And what’s so integral to the emotional weight of this design is that it could very well be a modern game. The central argument is certainly relevant today, particularly with the culture war raging in America.

Perhaps the modern reverberations are unintended. Regardless, it’s all too easy to view this game through the lens of present politics.

In a real sense I liken Molly House to the ludic equivalent of protest music. It’s something we haven’t seen much of, with a few small press imprints such as Hollandspiel functioning as primary drivers of a fledgling movement.

We have Woody Guthrie, Gil Scott-Heron, and Public Enemy.

Why not Amabel Holland, Jo Kelly, and the Wehrle brothers.

From virtually all perspectives, this powerful design can be interpreted as inspiration for protest and social change. It’s art with the intention of moving those who are open to such a thing. In this way, it’s the apex of what games should aspire to be, if they aspire to be anything meaningful at all.

A review copy of the game was provided by the publisher.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.

4 comments for “Burning Down the House – A Molly House Review”