Somewhere, Matt Leacock is walking around, chained to a big goose as gold as the sun. For the love of God, someone let this man design something other than Pandemic.

Not today.

While not betrayed on the cover, The Lord of the Rings: Fate of the Fellowship is described as a Pandemic System game. And that’s true, but only if you squint and crunch your face like an inquisitive hobbit.

The Leacock-ism does make an appearance. This is the signature mechanism of “shuffle these recently discarded cards and place them back atop the deck”. It’s subtle here and not as central to the experience. More evident is the tower defense-like structure of invading enemy forces that harkens to Pandemic: Fall of Rome. The implementation is more complex in Fate of the Fellowship, representing the Orcs, Southrons, Trolls, et al., rising from Mordor and invading the land of the Free Peoples. The increased complexity is immediately evident when taking a gander at the board, for the wide-ranging pathways form an intersection of routes that could only be more poorly designed if it belonged to The California Department of Transportation. It doesn’t help that the physical dimensions are surprisingly small, resulting in a reliance on tiny meeples and smooshed geography. This visual and tactile mess is the strongest criticism of the game. Don’t worry, you will get over it.

There are a couple of other little nods towards Pandemic, such as a shared player deck with cards bearing various suits as well as specific regions of Middle-earth. The locations simply restrict where they can be traded, while the suites are used for certain actions. There are also Skies Darken cards scattered throughout this deck, effectively replicating the evenly paced Epidemic triggers of its predecessor.

That’s pretty much it. Spaces don’t pop when they accumulate too many enemy pieces. Players aren’t trying to constantly accumulate cards of the same type in order to cure their plight. This doesn’t feel like Pandemic at all. Those coming to Fate of the Fellowship in search of that will be disappointed. What they find will be something else altogether.

Something greater.

Outside of the Legacy series, this is undoubtedly the masterwork of Leacock’s career. If that isn’t startling enough, it’s quite possible that this is the strongest Lord of the Rings game to date.

No, I will not shut the hell up.

I’m not sure of this yet. It may take years to come to a proper conclusion. But the fact that I’m even considering it is indicative of this game’s status.

War of the Ring is unquestionably more epic and significant than Fate of the Fellowship. That two-player wargame is phenomenal and has a fanatical one-of-a-kind following. However, I’m an oddball and have always held Middle-Earth Quest as best-in-class of all the Tolkien-inspired tabletop entries. That one-versus-many adventure game offers a more personal glimpse into the setting, and it blends several unique mechanisms to formulate a high intensity affair.

Fate of the Fellowship bridges the two, marrying the scope of War of the Ring with the intimate framing of MEQ. If you pay attention to what’s going on, it manages a grand narrative while allowing for side-quests and moments of brilliant story vignettes. And it does so with less rules density than either of those two games.

Take care, for this is not a straightforward or accessible design. Fate of the Fellowship is firmly mid-weight, its genes belying the foundational complexity. With four or five players at the table, this will go a good two and a half or three hours. This is a much more substantial game than many would expect. The primary driver of this mass is the objective system.

Every time you sit down to play your goal will be to get the One Ring, and thus Frodo, to Mount Doom. You must also possess a hand of five cards bearing a ring symbol, which then allows you to cast the cursed item into the hellfire of Mordor. There’s a dramatic dice roll, not unlike the pivotal moment of Phil duBarry’s Black Orchestra. Sometimes this moment is a dud as you have it locked in with little chance of losing. Other times it’s a stand up and hold your breath exercise. This is the good stuff and what gaming is all about.

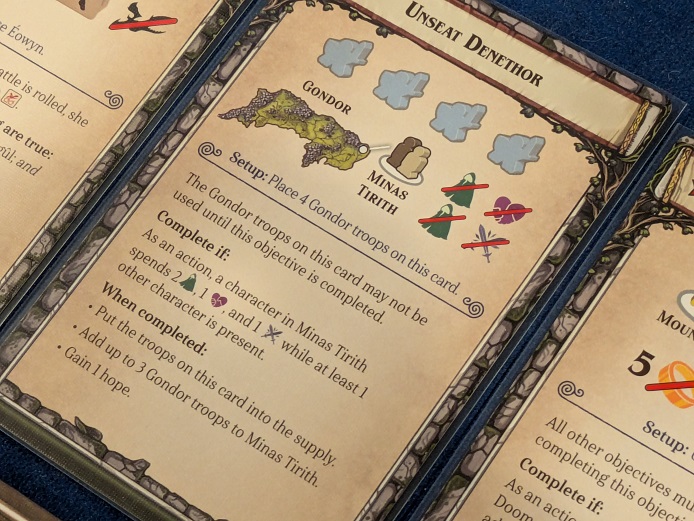

But there are other tasks as well. Missions you must accomplish prior to destroying the ring. These are beauts. They’re scenes lifted from the books and inserted as micro-narratives into this design. They’re randomized from a large pool as well, so you never know what you will need to do prior to the forming of the fellowship.

Boromir may need to find redemption by sacrificing himself heroically. Someone might need to visit Rivendell and attain the blessing of the Elves. There’s a chance you’re commanded to free Mordor from the clutches of evil or liberate Isengard with the help of the Ents. These are big story moments we’re familiar with, and a randomized selection will form the outline of each epic session.

These objectives are contained on large Tarot-sized cards. They’re wordy and multi-layered, often requiring multiple conditions to be met, such as discarding certain cards or clearing enemies from multiple locations. They offer rewards that are multi-layered as well, perhaps granting new troops or restoring hope, effectively buying you some time. These also create a barrier for new players, as it’s easy to lose track of what the group is trying to do or become overwhelmed with strategic pathways to consider. Placed atop the existing action system, card-driven enemies, and a multitude of character powers, it can be a lot.

Let’s talk about those characters. This is such a fantastic little twist. Instead of claiming the role of a single protagonist, each player receives two random characters. You are responsible for both, splitting each of your turns between them. However, you can’t afford equal attention. Every turn, one of your characters will perform four actions and the other just one. This is a clever micro-decision where the design flirts with additional player agency. Beyond the tactical implications, it allows for a wider cast instilling a larger scope in the game than would otherwise exist. It’s such a smart inflection, as it enhances the overall richness of premise while also adding texture for each participant to wrestle with. This device is one of the most important elements in the game, as it coalesces with the objective framework to capture that epic quality that is often elusive in games like this. Without these details, it would lose any semblance of comparison to War of the Ring.

The automated enemy system is just as interesting as the dual-character method, although it lacks much of the finesse. After each player takes a turn performing their actions, cards are flipped from the top of the Shadow deck. These have one of two effects: they either move enemy forces along one of the board’s colored pathways, or they place new troops in a Shadow stronghold and shuffle around the Nazgul. We will get to the Nazgul, give me a second.

There’s a neat little detail where the top or bottom effect of the card, each paired to one of those two previously mentioned action types, is determined based on the top of the draw deck. So, you turn over a new card, then look at the next card’s back, which tells you to execute either the top or bottom of what you just revealed. It’s nifty. I wouldn’t call it innovative, but it’s neat.

What holds me back from outright praising this schema is the amount of administration involved. You need to look at the drawn card, find where on the board it’s referencing, then move several small stacks of meeples along a path. Sometimes you bump the Nazgul miniatures and create a little chain reaction of displacement that needs to be cleaned up. I wouldn’t call this arduous, but it’s certainly a chore without the promise of an allowance. You also have to do this several times, with the number of Shadow cards increasing over the course of play.

Alright, about the Nazgul. In an astounding stroke of insight, Leacock formulated this game around the transport of the ring and evading the Ringwraiths. It’s the heart of the design, operating under a similar ethos to the narrative objectives and character implementation. It provides a personal perspective by requiring Frodo to toss some dice and evade capture every time he moves through dangerous locations. Nazgul and troops create pressure points, with increased numbers forcing larger pools of dice. Primarily, this resolution will deplete Frodo’s hope, threatening to push the fellowship to the brink and trigger a loss. You feel as though you are in constant flight. Your pursuers never let up, and all you can do is seek to hide or escape unscarred.

This instrument is a huge driver of the tactical weight. Frodo can move alone, sure, but characters can also escort the ring-bearer during their turn. Sometimes you may want to utilize troops to clear a pathway and secure the road. This creates a puzzle of sorts, one that intermingles with the penetrating narrative to create scenes of tension and risk. Steadily, the game zooms down to a set-piece like Weathertop or Moria and gives your emotions a yank. This flipping between macro and micro settings is similar to a startling jump of aspect ratios in film. It’s jarring, but also intense and deliberate. It’s a wonderful way to frame the action. It draws your investment down to the stamped dirt, smashed hay, and scattered bones lining Middle-earth’s crust.

Time to come clean. I’m writing this review principally to discuss two things. It took me 1500 words to get here, now let’s see if it’s worth it.

The first is how this game expertly wields intellectual property. It’s a model case, leaning into the strength of its literature for maximum weight. This is a game, ultimately, for Tolkien fans. The broad strokes of narrative – supplemented by those precise bullet point objectives – are legitimate primer for wondrous anecdotes. But they rely on the player to supplement the experience with the context of the novels or films. This background information brought to the table by the players is crucial context to bring the game to life.

Frodo, Sam, and Gollum splitting from the Fellowship and trudging through Ithilien while beset by Nazgul. Boromir leading a desperate charge into Isengard, sacrificing himself to draw the eye of Sauron and provide an opening for the hobbits. Gandalf riding upon Shadowfax through the North and raising an army to uplift a siege in Rohan. Aragorn rushing to meet with Theoden and free his mind from rot. All of these are much more vibrant and expressive when one supplements the in-game actions with their out of game knowledge.

It’s a masterclass in weaponizing the setting. Leacock provides broad strokes, confident enough in the player to do the rest. This unburdens the game, allowing for brevity in the story elements and background, freeing up that design budget for alternative uses. Unfortunately, the downside here is that those indifferent to Lord of the RIngs will not glean the same satisfaction and appreciation that I detail in this review. You likely won’t piece together the grand narrative that’s occurring. You won’t point to certain board states and emergent situations and connect the outlines of story into something greater. This calls back to the idea that this is not a Pandemic game. It’s a Lord of the Rings game, above all else. Those who have no interest in the property will likely wonder what the rest of us are gleaning from its contents.

The second angle I want to examine is Fate of the Fellowship’s narrative structure. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this game. In doing so, I keep coming back to an inherent connection to Star Wars: Rebellion.

Both games seek to tell stories lashed to iconic and seemingly rigid properties. These are novels and films that people hold dear and care deeply about. As tabletop adaptations, they combine emergent narrative with semi-prescribed scenes in order to invoke those embedded emotions. In Rebellion, a character can visit Dagobah for instance and train as a Jedi. You can even construct the Death Star and blow a planet apart. It’s full of these absolutely radical moments that define the game, and it commits wholly to this dynamically generated reenvisioning.

Fate of the Fellowship has some of this. Its induced moments are less grandiose, but they’re there. The fellowship can travel quickly through Moria and confront the Balrog. Eowyn can fell a winged beast, permanently reducing the number of Nazgul. There are dozens of these vignettes, their inception courtesy of the brilliant objective system.

But this comparison has never felt right. There’s something off. When studied closely, the storytelling methods are different.

Rebellion serves as a script generator. It’s a tool to create a Star Wars story that is unique and personal, constituted from a variety of pieces supplied by the game. There’s a tremendous amount of freedom given to the players. In a sense, it’s a reboot machine. Every play of this game crafts a bespoke reboot of the Original Trilogy, one which is faithful, logical, and passionate. The walls of the sandbox keep the tone and story beats within a certain threshold, but it never restricts your creativity. Vader can capture Mon Mothma and torture her on occupied Alderaan. General Dodonna can lead an offensive on Tatooine, shattering the Imperial fleet by destroying the Executor. Leia can turn to the Dark Side, taking position alongside the emperor and commanding the ground invasion of Kashyyyk. It celebrates artistic autonomy. And it’s better for it.

Fate of the Fellowship isn’t that. It’s more straightjacketed, providing a range of randomized scenes that may occur. But these scenes are more narrowly prescribed. Aragorn can’t take Boromir’s sacrificial place. You can’t convince the Ents to rise up and lead a siege into Mordor. Gollum can’t become the ringbearer and fulfill the mission. It offers leeway, but within tighter and more defined boundaries. Much of the freedom is granted on the macro scale and outside the objective system. You can’t so much reboot Lord of the Rings, but you can exaggerate or twist elements of the story. You can tell the epic out of order or alter small details. In essence, you can mis-remember it.

This game isn’t about rewriting the tale. It’s about oral tradition. Through play, the group is engaging in a transmission of culture, formulating and telling a story which they already know. You can make small adjustments, such as the fellowship bypassing Moria and instead heading South out of the Shire, but you can’t redefine the main elements. You can make it your own by reforming certain details or reshaping the liminal matter, the things lingering in the soft space between the milestones. It’s as if you’re recounting the story on a dark night with your senses diminished, relying on blurred memory as you blabber about in between gulps of mead. But what’s important is that you are doing the recounting.

Fate of the Fellowship isn’t about creating something new. It’s about the preservation of a beloved and important mythopoeia. It’s about celebrating something influential and culturally significant, with play synthesizing the role of oral tradition.

And thus, I again must ask: Is Fate of the Fellowship the best of its ilk?

A copy of the game was provided by the publisher for review.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Matt Leacock for a Game Developer Conference presentation I gave a couple years ago. The guy is an incredibly smart and capable designer. Really cool to hear he was behind this game!

I’m most excited about your analysis of the procedural/emergent narrative and how it is accomplished. As I work on the corresponding part of a new game design, I’ve been comparing Eldritch Horror, Elder Sign, and Arkahm Horror LCG, 3 games with the same IP and setting, all of which generate procedural narrative differently. I’m interested in which mechanics and content design constraints they use to accomplish different outcomes. Similar to your very apt Star Wars: Rebellion vs Fate of the Fellowship comparison.

So much of emergent narrative is how the game lays out tokens and then gestures to connections between them so that the players can fill in the gaps with sequenced events, causality, and meaning from their imagination. It’s an art that board and card games are on the forefront of mastering.

I bet you have a existing set of thoughts about emergent narrative?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s very interesting, Randy.

“So much of emergent narrative is how the game lays out tokens and then gestures to connections between them so that the players can fill in the gaps with sequenced events, causality, and meaning from their imagination. It’s an art that board and card games are on the forefront of mastering.”

That’s such a clear and sharp quote. I totally agree that this is something board games do incredibly well, and it contrasts strongly with the things board games tend to struggle with, like hugely woven and lengthy narratives constructed through text.

I greatly prefer emergent to prescribed narrative. This has to do with that last point, but interacting with prewritten text and a prescribed story can harm the agency of players, it also takes their actions out of the spotlight, limiting creativity and investment.

There are some fantastic games that lean into prescribed narrative, such as Tainted Grail, Tidal Blades 2, and Legacy of Dragonholt. But the stories told in games that germinate emergent narrative are more personal and emotional. There is a sense of investment through the act of creation. The stories we tell together tend to resonate more strongly than the stories we listen to someone else tell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As someone who leans very heavily into thematic games, I find this subject fascinating. But I wonder if board and card games are actually on the forefront of mastering emergent narrative. There’s been a glut of story-driven games the last few years that often just glorified Choose Your Own Adventure paragraph-picking, and while I definitely agree that emergent narrative games are usually far more fulfilling and memorable, there seems to be very few games that really explore that style successfully because it’s a far harder and more nebulous route to travel. Western Legends? Nemesis? Merchants & Marauders? Escape From New York? Maladum? Do you have any favourites in this style Charlie?

It feels related to the ‘show don’t tell’ principle in filmmaking (so often trampled on in this age of voiceover narration). Creating your own story through the gameplay is so much more satisfying than just reading reams of text and following the prompts with the occasional ‘skill test’ thrown in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Show don’t tell” is a perfect comparison.

My favorite emergent narrative games, off the top of my head and in no particular order, include:

Nemesis

Western Legends

Earth Reborn

Merchants and Marauders

Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Slaughterhouse

Battlestations 2nd edition

Conan

Maladum

Cave Evil

Star Wars: Rebellion

LikeLike

You’re right to say that lots of board games do this “badly” (or more fairly, don’t attempt quite the same thing we’re talking about), with the CYOA comparison being apt.

I work in video games, with a career emphasis on emergent narrative (eg – the Thief series). Video games often do emergent narrative very well with respect to low level mechanics and action gameplay – physics, combat, racing, etc., and they typically accomplish this with enormous systems that would never fit in a board game.

The downside is that video games are just as stuck (more so, really) than board games when it comes to higher level emergent narratives – stories about solving a mystery, romance, interpersonal conflict, self-reflection, etc., or even just the top-level arc of a plot. These are concepts that are hard to capture meaningfully with a big complicated system, so they tend to be baked with very little interactivity.

Games like Nemesis and Merchants & Marauders mostly take the video game approach – they provide meaningful freedom in low level, mechanical interactions like movement, shopping, combat, etc.. Think of the Mission cards in M&M – the narrative flavor there is an excellent addition to the game, but it’s not very interactive. Put another way: the decisions a player makes about how to acquire and trade goods at different ports, or whether to scout for and attack merchant and naval vessels, is nuanced and offers a rich tapestry of options and consequences. But on a Mission card, the bit about helping a bride elope to her beloved (or whatever the fiction might be) is take-it-or-leave it. It’s not like you have the option to seduce the bride, or rat her out to her possessive father, etc..

I’m really interested in games like Eldritch Horror and Robinson Crusoe which meaningfully strive to produce emergent / procedural higher level narrative. Here’s what they do well: as a player, I feel like I got involved in my own story of researching clues in an ancient stained glass window, negotiating with unearthly guardians to let me into the underworld, improvising my way through a theatrical play where I’ve never seen the script, convincing the Vatican to give me their blessing, etc.. And more importantly, I invent my own narrative connections between these: one time I had the ex-convinct character delayed because he got too tempted and tried to steal an object. He’s good at stealing but bad at convincing the cops to let him go when he was caught, and he was crucially needed next turn in the Amazon to fulfill his part of the quest. The emotional weight around this interaction came from the specific character and the context: it would have been a very different story if Sister Mary had drawn the shoplifting card in a moment of less urgency and had succeedeed her stealing roll.

So, having studied and attempted to understand this game design, I think it comes from highly specific story moments (“your character is shoplifting to steal a magic item”) combined procedurally at “runtime” with other tokens (specific characters, locations, etc.) inside an overall context (our current moment of quest urgency) combined with a lot of vagueness about everything else – those are the gaps that the player fills in with their imagination to tell the rest of the story. I believe all thematic games do this: when you look at a MTG creature, you read its stats and look at its image, and invent a bunch of details about what exactly this creature is like. Being part of the creative process is part of the appeal of board games.

Here’s what these games don’t usually do well: within a given story moment, there’s usually not a lot of meaningful interactivity. I can pass or fail my stealing roll. In rare cases I might be given a branching option to attempt to steal or do something else. But that’s at most, meaning the tokens are pretty atomic. I can’t intentionally set out to shoplift, it’s something that happens TO me. I can’t decide to sneak past the unearthly guardians instead of negotiate with them. So the emergence is more in how the story unfolds in my mind in a rich way, compared to Nemsis or M&M where I can decide on my every action.

One last thought, though: I actually think it’s all the same and only different in granularity. For example, when I shop for goods at port in M&M, I can’t haggle or attempt to steal goods. The game is careful in not suggesting that’s something you should want to do, by making that part of the interaction very perfunctory and mechanical. If every time you shopped at port, you had to draw a narrative card and read what your shopping experience is like, you’d wind up with a richer story but more places where you felt like you should be given more freedom and choices. But it would mechanically be the exact same game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is a lot of good stuff here, Randy. I was thinking about this the past few days, and it pushed my thoughts into several different directions. As someone who has a deep background in RPGs and constantly compares and contrasts them to board games in terms of how I think about and process these experiences, I wholly agree on your statements about board games not offering depth of interactivity. Your options and the results are somewhat straightjacketed, limiting narrative agency.

The bits about purposely placed vagueness for players to fill in is important to allowing for the flexibility in this medium, and it’s what emergent narrative more compelling than prescribed narrative in my opinion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also started with games playing RPGs (way back in 1978), and it’s always peeved me that video games started calling themselves RPGs (leading to the ultimate indignity of pen-and-paper RPGs being forced to re-label themselves TTRPGs!), as it does when board games try to use the same descriptor. Video games and board games simply can never even come close to the almost complete freedom of storytelling that RPGs offer, and it’s just marketing-speak for those types of games to pretend they do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with you! I think pen and paper RPGs are just a different artifact than video games or board games.

Video games and board games I would group together in the sense that the designer creates a static offering, created and limited by the rules which are inherit to its existence, and hands it to the players who then explore it at “run time,” learning the ins and outs and interactive variety and how all that adds up to a single thing (which I call a “possibility space”). A book or a film may be less interactive, but they have a lot of similarity to video games and board games in this sense – there’s only content in there that the designer created, whether explicitly or unknowingly. (Side note: board games are just like video games, but the “hardware” they run on is computers for one and humans for the other).

RPGs are a different thing altogether. The rules do not create or limit the experience, they only offer some amount of guidance. This cultural artifact instead revolves around person-to-person interactivity, so it’s a lot more like a chat room, or improv theater, or an exquisite corpse. The rules help give a sense of objectivity, but they are not rigid even a fraction to the degree they are in a board game or video game. Some people see downsides to this – there’s a sense of loosey-goosey-ness to RPGs. But one clear upside is that they are unlimited and anything is possible in a way that board games and video games cannot even approach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damn you Charlie, I was hoping you wouldn’t like this one – now I have to get it! 🤣

I’m pleased to hear it has little relation to the Pandemic games (I really wish they wouldn’t slap that label on it if it’s not accurate – remember Star Wars Risk?), and while I’m really not a fan of the graphic design style here, your praise is too high to ignore. Thanks for the review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I think you will definitely appreciate this one, graphic design notwithstanding. If you end up making a video, I look forward to watching it.

LikeLike

This sounds amazing! I love The War of the Ring dearly, but I’d be so excited to play something similarly epic with a character- rather than army-focused approach. This might just be it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This definitely doesn’t touch the achievement of War of the Ring, but it’s eminently more playable, and it has a strong character focus which alters the feel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review. I think your framing of the narrative of this game perfectly captures what makes this (relatively simple, fast playing) game so compelling to me. This will never equal War of the Ring in my eye, but it is much more playable and does a pretty good job of telling the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Christian. I appreciate you reading my review and taking the time to comment.

LikeLike

I picked this up a few days ago and hope to get it on the table in October. I’m having my first “ToddCon” which is a weekend with some friends to just play games and I’m putting this on the list of games, along with Last Night on Earth. 🙂

I own 1st and 2nd Editions of War of the Ring and that game is spectacular, but I don’t play it often. I actually use the 1st edition minis to use to play the expansion “Battles of the Third Age” which is essentially two war games, Helm’s Deep and Minas Tirith.

Anyway, this game really intrigues me and based on your comments and a few others I follow, I expect to love this game a lot. I like games in the 2-3 hour range and this sounds like another good one for that game length. Also this allows for up to 5 players and currently my only opponent for WotR is my adult son so I think I can get this one to the table more often. Nice write up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good luck at ToddCon! Hopefully you dunk the ring into Mount Doom, and if not, hopefully your journey is epic.

LikeLiked by 1 person