Philosopher Mara van der Lugt’s 2025 book Hopeful Pessimism challenges ideas of motivation and the role of despondency. It’s a revelation of sorts, especially for those plagued with eternal pessimism.

That’s me. A relentless worrywart, down to my bones.

Van der Lugt argues that it’s possible, nay encouraged, for those suffering from pessimism in a broken world to strive for change without certainty. She pushes for an ethical oriented hope that is foundational on the values of the effort itself, not on the outcome. It’s about responsibility and action, directly opposed to nihilism. Should we continue to fight even if success is virtually impossible? Hell yes, we should.

This is a theme commonly proliferated throughout storytelling. J.R.R. Tolkien’s work is cited by Van der Lugt as a prime example. Frodo and Sam act out of courage and duty, despite the overwhelming odds and high probability of failure. Their sacrifice is something we can all aspire to and envy. In many ways, this way of thought is a call to action.

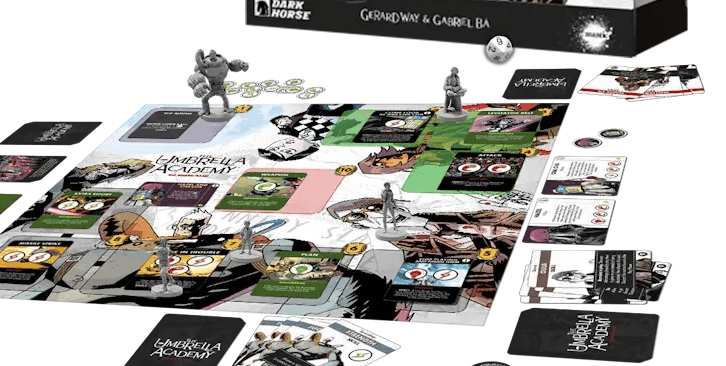

I also see this motif reflected in board gaming. Not simply through a connection of meta theme and setting intertwined with systems, but in a more basic and foundational concept of high difficulty. Particularly, I’m talking about the degree of challenge in cooperative gaming.

There seems to be a trend in the past several years of cooperative hobby board games having a steeper difficulty, if not by default, then by the encouraged ability to throttle this trait. I’ve heard other reviewers, such as The Dice Tower’s Tom Vasel, complain that too many games are currently tuned to a grueling level. Ghost Stories and Space Hulk: Death Angel are two pre-2010 releases that stood out as arduous and grew an identity from this quality. Now, there are a plethora of titles with a similar approach to setting a high obstacle. Games such as Robinson Crusoe, Kingdom Death: Monster, Spirit Island, Gloomhaven, Regicide, and so many more.

In 2025, we want to get kicked in the teeth. We’re directly asking for it.

At least I am.

When I sit down to play a cooperative game for the first time, I need to lose. Yes, it’s not a desire but an imperative. If I overcome the obstacles set before me while I’m still coming to grips with the system, where is the satisfaction therein? I bested something while fumbling around, like an oblivious Jar Jar Binks sacking battledroids one blunder after another. If a game puts me into the bumbling idiot role, then it better expect a similar level of respect in turn.

The inherent structure of opposition in cooperative board games is that of a puzzle. Since any form of artificial intelligence in such a game is necessarily rudimentary, it can’t respond or adapt in sophisticated ways. Instead, it offers challenges. At best, it can be unpredictable and increase tension over the arc of play. Because the typical obstacles in a cooperative game are primitive, they present an optimization puzzle for players to solve. Puzzles are only satisfying if they require a suitable level of thought. A puzzle easily conquered is nothing. It’s busy-work. A roadblock to the good stuff instead of the good stuff itself.

There are exceptions, primarily with the genre of narrative games. When engaged in a dramatic and rich story, challenge is able to take a back seat and become de-emphasized. I’d still prefer an epic narrative game to not be exceedingly easy, but this failure can be softened if the narrative delivers me to a special place. Welcoming games and those aimed at a wide range of skills and ages are also exempt from this desire of increased challenge. These are not the types of games I’m framing this discussion around.

The standard hobby cooperative game greatly benefits from high difficulty. It sets the tone of play, uplifting the antagonist forces and establishing a hostile relationship. This can lead to emotional investment, eliciting disappointment and anger. When those ‘Nid Genestealers tear down your last marine, you’re either seething or grief-stricken. As there’s not above the table play or another being to engage with on a higher level, it helps to establish a relationship or history with the intelligence systems through conflict and abuse.

Fortunately, fostering such a negative response does something else. It creates an equal and opposite reaction when victory is achieved.

This is where Van der Lugt’s philosophy most closely connects with the idea of steep challenge. By setting the difficulty to a formidable level, it promotes an integral pessimism. Games like Regicide and The Mind begin with the premise that you will lose. This increased threat is an essential element of the game’s characterization and everyone who has even a lick of experience approaches with the correct pessimistic assumptions. We expect defeat and we play them anyway. And there is valor in that mindset.

But then something wondrous happens. We actually win.

The act of continually losing, of facing insurmountable challenge, it enhances the satisfaction of victory. It heightens the emotional payout. My fondest memory of playing The Mind isn’t that time where I was dealt a straight run of 33-35, it’s the time we actually won. I recall the shouts of joy, the group connecting in that moment of triumph, and a deep level of gratification emerging from the tension. It was glorious, and that’s because it felt like an impossibility.

However, success is not all. Crucially, the act of playing and the pleasure derived is not predicated on this result of victory. Were not all those sessions plagued by failure a worthwhile endeavor? Were they not a source of contentment? The hope is critical, not the achievement.

As Van der Lugt posits, there is value in the effort itself. The exertion is the act of heroism. Despite the bleak outlook, and the slim possibility for exaltation, just playing the game and banging our head against its bastions is enough. This is everything we can expect from the experience, and nothing more. More is a bonus.

Toiling away on something only to fail is a reflection of the human experience. Failure is a natural state of our existence. These are the moments where we can learn something not only about systems, devices, and narrative, but also ourselves. Moments of impossibility are when we come together. They’re when we lean on each other and when we are most vulnerable.

We must strive despite this desperation. We must adopt hopeful pessimism.

I want to leave you with the last words of Jane Goodall. “Don’t lose hope.”

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

Really excellent post! Gives words to the feelings I have towards the (often) near-insurmountable challenges in cooperative games, the pull I feel in coming back to them, and where I find enjoyment in those moments too. Thanks for connecting it all with Hopeful Pessimism!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Mike! I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

LikeLike

Just wanted to leave a comment to say I love your writing. I stumbled upon this website 2 years ago and have been following it ever since. Really good!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Henry! That means a lot to me and I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

LikeLike