There’s this thing that people say which rips my skin like 60 grit sandpaper.

“That was fun, but it’s not much of a game.”

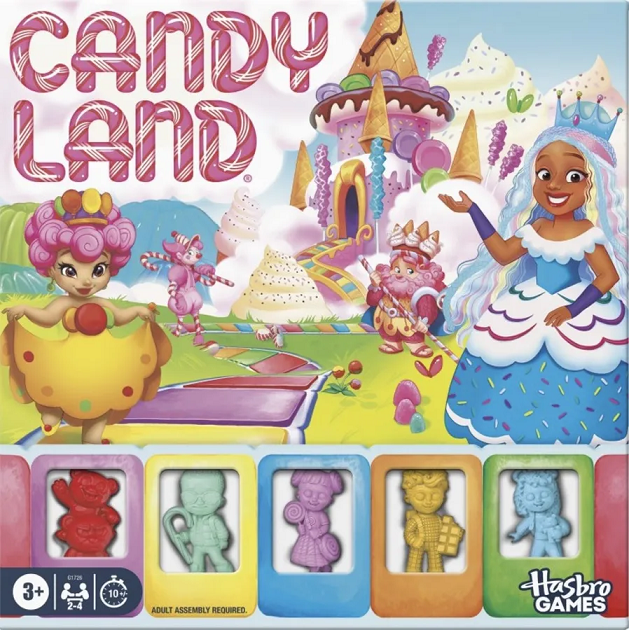

Games require decisions. Meaningful ones. At least, that’s what a portion of the hobby community believes. Candy Land isn’t a game they say, it’s an activity. There’s an obvious implication that these low agency games are subservient. They’re relegated to the pen of sewerage that encompasses coloring or fort building. First of all, coloring and fort building are rad. Second, you’re wrong. Full stop.

Candy Land is just as much of a game as Twilight Imperium or Brass.

There’s an elitist tinge to this way of thought, whether intentional or not. I see no purpose in restricting the classification of game to something with meaningful decisions. If someone is looking for Chutes and Ladders, which store aisle are they going to? Arts and crafts? No, of course not.

Underlying this poisonous ideology are the core tenets of existentialism. Existentialism is a philosophy which emphasizes individual freedom and creation of one’s own meaning. It’s about empowerment and agency. There’s a presupposition that humans are born without purpose and must subsequently find their essence through choice.

This uncompromising emphasis on freedom necessarily places the human at the center. The agent and one whose actions author intent is placed on a pedestal. This is reflected on the tabletop through the players, operating within the scope of the rules to influence the outcome. In board games players often accomplish this via interaction. Cooperation and conflict intermingle these disparate agencies and produce greater meaning.

Another element of existentialism that is reflected in board gaming is the idea of the absurd. This is the contrast between the individual’s search for meaning and the inherent lack of such in the universe. That distinction parallels the dual state of agency within the scope of play and the sharp transition to post-play, where the rules and decisions and story fade, giving way to reality. These contrasting states of manifestation within the magic circle and the sober vacuity of life are a whiplash of sorts.

But here’s the rub, existentialism is most applicable to a sub-type of game. This notion makes me think of Galaxy Trucker or Vantage. It doesn’t wholly encompass all of board gaming. Viewing games without decisions as lesser activities is petty at best and nihilistic at worst.

In just the last couple of years we’ve seen a resurgence in roll and move as well as other low agency designs. I’m enthusiastic about Damnation: The Gothic Game, Magical Athlete, and Hot Streak. All of these games are absolutely killer. Who needs the weight of economic hardship in 1800s Birmingham when you can scream at a person in a hotdog suit. The joy of board gaming is not defined by intellectualism. Joy is an emergent property that can arise from kinetic, aesthetic, and psychological forces. Screw meaningful choices. I want meaningful play. Meaningful experiences. None of this requires decision trees or complex calculation.

There is another way to look at it. It’s not impossible to frame existentialism positively in light of these low agency titles. They’re not entirely mutually exclusive. The experience that arises from interacting with a game and its rules can be examined for meaning. Discovering purpose in such a way is in fact a principle of existentialism, whether meaningful choices are few or plentiful.

Would you believe me if I told you that even Candy Land is loaded with meaning?

Eleanor Abbott invented Candy Land in 1949 while she was recovering from polio. Through her own pain and suffering, she crafted something beautiful to provide an escape for children enduring this disease. Its color-based simplicity intentionally requires no reading or complex rules understanding. Very young players could gain a sense of freedom and movement that they could no longer experience in everyday life. Even the saccharine setting was established with intentionality, providing a fantastical world intended to immerse and distract these kids from their illness.

Candy Land is a game stuffed with purpose. What it’s not stuffed with is decision making. You draw a card, match the color to the next available space on the board, and move your piece. But this is fundamentally a game, regardless of its lack of sophistication. I’d go so far as to state that its humanitarian goal is more powerful than any intentionality found in serious games. Quite frankly, Candy Land is more significant than Ark Nova or Gloomhaven or a dozen other highly rated titles.

Look, the existentialist position rooted in player agency is a worthy pursuit. I enjoy those types of games and value input into the shared experience. But we can’t be subsumed by arrogance. Board gaming encompasses a wide range of activities that appeal to various proclivities and temperaments and ability levels. Narrowing the boundaries only causes harm and confusion. It makes discussing this wonderful hobby challenging and it fosters division. The end result is absurdity. In which case it only becomes harder to find meaning and manifest purpose.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

Well said. I believe that the goal of playing a board game should always be to have fun, and different players may find different levels of enjoyment in various games. A friend once lost a turn while playing Arkham Horror. He was frustrated, but accepted it. Then he lost his next turn (I think this happened at the retirement home for sailors in Kingsport, where residents can cause lost turns with their long-winded stories), and everybody at the table started talking about how losing a turn was bad and archaic game design. Then he lost a third turn in a row at that same location, and we all laughed long and loud, so it was worth it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That sounds a little rough, but glad it turned to humor and everyone rolled with it.

LikeLike

hey ! Great things here. Glad to see this kind of text. By the way, imo, Trivial pursuit is not a game. No meaningful choice at all just a good amount of memory.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Point taken. And I generally agree with you on the humanistic emphasis of existentialist worldview. I suppose my question in response, though, is what do you suggest the answer is here? You rightly criticise existential self-righteousness, and even suggest meaning and joy are things that “arise.” But is there, then, an Originator of such meaning and joy? The history of of Candy Land, I would say, points to the fact that in the work of creativity, meaning is thus given by the creator. My own view as a Christian is that this reality is a reflection of the Creator who instills in all of His creation an inherent dignity and beauty that only a Creator can. Play, community, fellowship—all these and more surround the square piece of cardboard sitting at the centre of the table. And if joy arises out of that regardless of the content on said piece of cardboard, then, as you suggest, the game has done its job.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m a former Catholic who attends a Christian church a couple times a month, despite classifying myself currently as agnostic.

With all that being said, I can get along with the idea of a divine spark existing behind the creation of artistic work. If God doesn’t exist, then that divine spark may simply be an intrinsically human spirit responsible for creativity and purpose.

I intentionally left some of this out of the piece, as well as a definition of “game”, in order to inspire a reader to come to their own conclusion.

LikeLike

I honestly don’t have an article of yours that I don’t like, but I especially like this one. I loved Candy Land as a kid. When I had my kid, my parents gleefully gave me Candy Land, laughing about how now I could endure this travesty of a “game” and “see how it felt.” I laughed…and then proceeded to thoroughly enjoy playing with my kid as he was 3, 4, and 5. I marveled at how it helped teach him how to handle things with care (not bending the cards, not flipping the table, and treating himself with care too – not yelling or dissolving in sadness). I appreciated the opportunity to remember that its our game and we can house rule (once the characters have been seen, they leave the deck so you can’t eternally be shoved back to Mrs. Nutterbutter).

Now we play Warhammer and Cosmic Frog and Oath, and I won’t pretend that Candy Land had some hidden strategic element that welcomed those games. But he learned how to pick cards off a deck, how to put them down without snapping them / creasing them, and how to be a mostly pleasant opponent.

I was also aware of the history of Candy Land and it’s marvelous that that simple joy can still be enjoyed. On a tangent, have you read the marvelous book about the creator of Monopoly? Parker Brothers sure ran her ragged.

I love the FUN of Bushido and I can’t stand the thinky-ness of Brass. I appreciate that Brass is a “good game” but the subjectiveness of joy shouldn’t be trampled on by elitism.

I always appreciate your welcoming approach and clear writing, Charlie!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, John. Your words are mighty kind and I appreciate them.

I love hearing that story about you and your kid. I had a similar experience with my daughter who is now 12. She no longer is into games – I surely failed somewhere along the way – but she was super into Candy Land as a toddler.

I personally don’t enjoy the game too much, but I respect it and think it has a clear purpose, which you expand upon in your text.

I am aware of the Monopoly story and how Elizabeth Magie’s Landlord’s Game was ripped off. Very sad story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We self-reflective, academic types have an urge to perform taxonomy on things we’re interested it. But it’s entirely possible that “What is a game?” is an interesting but silly question. When little kids running around on the playground organically weave a light sense of structure in and out of their playful activity, are those games? When one early human hits the ground rhythmically with a rock and another responds with a counter beat because it’s interesting to them is that a game or music? Are TTRPGs with no rules games, improv theater, or conversations? Does it matter? What would be accomplished if we were to find a crisp dividing line between games and something else? Is it okay just to agree that things have varying amount of game-like qualities?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, exactly Randy. I would argue it’s better to maintain a more liberal and fuzzy definition than one which is rigid and restrictive.

LikeLike

Well said. I’ve always found categories (and review stars or numbers too, by the way) meaningless, especially the big ‘Ameritrash’ and ‘Euro’ debate (further categorising games by country labels was a further silly and inaccurate step). The only categories are those that people impose on themselves because of their personal likes and dislikes. The rest is just the endless fallout from Victorian-era principles of cataloguing and categorising in an attempt to put the work into neat little controllable boxes. I play all kinds of games from simple vintage games to incredibly complex ones, from RPGs to board games to tabletop miniatures games, and everything in between. My only personal categories, such as they are, are a good way to spend time and not a good way to spend time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Holy crap, what an insightful post!

I have nothing intellectual to add to it, but just wanted to thank you again for your reviews as well as greatly-reasoned posts like this one

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, I appreciate the kind words!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this call to community and inclusivity!

Currently I have my two nephews visiting for the weekend. One is 10 and DMs his own D&D group. The other is 7 and can’t sit still long enough to roll a die. Tonight we cracked the EXIT advent calendar and I was amazed to watch them plow through one puzzle after another in a crescendo of excitement and genuine cooperation. Arguing over what to label the box is beyond foolishness.

Agency or luck? Free will or determinism? Game or activity? Art? None of it matters. If it brings us together and supplies the feels, who cares if it was Terra Mystica or Slappy Salmon? I have room for both on my shelf.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well said, Gobbo.

LikeLike

I am deeply appreciative of all your work, Charlie, and the thoughtfulness you bring to the space of board games. I am also appreciative of all the responses to this piece supporting it. But I wanted to present a differing perspective, mostly because I’ve been thinking about this piece since you posted it and I feel I can best honor your considered words with my own, egotistical as that may be.

I see some core premises of the piece as:

1. We use the claim that something is “not a game” as a way to demean or diminish that thing

2. Candyland is deserving of attention and credit; it is a meritorious work, as much as or moreso than many supposed “games”

Therefore, one conclusion is: We should not call Candyland “not a game,” or use it as an example of “not a game,” because doing so diminishes the value of truly worthwhile works.

I want to break these premises apart, though, to draw attention to them separately. I agree that Candyland is a meritorious work deserving of credit; that it is valuable and a positive force in so many lives. I agree that often the claim that something is “not a game” is used to demean or diminish that work. But crucially, I do not agree with that conclusion. I think that Candyland is not a game, it is something else, maybe a toy-game or a learning tool; I also think it is very valuable; and I also think that we should stop using “not a game” as a term of disparagement.

I have a few of the young-child-oriented Haba games (and I use that term to describe them because that is, indeed, how they are marketed, and it feels common sense to use it!) that I play with my 2-year-old. Well, “play” is probably both the right and wrong term; I don’t mean it the way we mean it with games, but I do mean it the way we mean it with toys. We don’t really follow the rules of My Very First Games: First Orchard. She’s only two! We pick the cute wooden fruits up, and she throws them in baskets. I try to get her to roll the die. I try to explain the procedure as we “play,” but ultimately, she just likes the pieces and moving them around and giving them to me and her mom.

Obviously, this is all wonderful! I love that she plays with it. I love that she went and grabbed it the other day so I could open it and she could play with it. It is doing exactly everything I would ever want it to. But in this case, the way we’re using it, it is definitely not a game, but a toy. I am trying to rely on a useful definition here, where a game comes with a procedure, a set of choices/inputs, and a goal—an agency, as C. Thi Nguyen says in Games: Agency as Art—and a toy just is, to be used as the user desires. Toys are amazing! I love that they built this box with components, knowing they would be useful both as game pieces and as toys! It’s so clever, such brilliant product design.

Were we to actually play with the stated rules and procedures…it would play out fairly similarly to Candyland, in the way that most criticize. You roll the die, and something happens because of the result, and then you do that again. No one ever makes an actual choice. So, in that regard, First Orchard is just as “bad” as Candyland, yet obviously, it’s nonsense to somehow say that. First Orchard is a tool for me to spend time with my daughter, having fun, while also helping to develop skills. Turn-taking, procedure-following, whatever. It doesn’t actually have an agency because at no point do you have any input, but who cares?

I don’t need First Orchard to be called “a game” for it to be excellent.

Why, then, deny it its status as a game? Especially because I casually called it one earlier; it felt natural to do so! My reason is specific to my position to games in general, but it is the root of my desire to push back. I work in the larger games industry. I want to talk about what is and is not a game, where the line is, not to disparage the “not games” but to expand my understanding, to think about what is essential and non-essential, to ask “Where can I push the boundaries? Where ought I rein it in?”

Calling First Orchard or Candyland “not a game” is useful to me because it says that if I am trying to design a game, I should look at them and ask, “Why aren’t they games?” And I should use that knowledge to push the design of a game. Similarly, if I wanted to make some wonderful object with a different purpose, I can say, “Well, it isn’t important to add choice and decision-making into a toy-game I am making literally for 2-year-olds, is it?”

I think of it very similarly to jazz improvisation, or the kind of writing created by Joyce. My jazz teacher would always say, the art of improvising is turning a wrong note into a right note. Jazz improvisers don’t just play any notes at all; they have a deep understanding of music, be it intuitive, self-taught, or learned academically, that allows them to turn almost any note into a “right” note. The process of becoming a talented improviser is the process of first hearing what notes sound “right” and what notes sound “wrong,” and only then learning that the “wrong” notes can be made “right,” that the division was never so firm or real.

Similarly, many writers who play with language and write seeming unintelligibly—thunderwords, I’m looking at you—first learn all about language and its rules and what feels right and wrong. Their ability to then push back on those rules doesn’t come from a lack of knowledge—it comes from a deep and abiding knowledge! You have to first learn the rules to know how and when to best break them. (I even have had many discussions about superhero deconstructivist narratives like Watchmen, with the important realization: Alan Moore created the greatest work of deconstruction of superheroic narratives because he knows those narratives and even loves those narratives so well. His other works, such as Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, show this.)

So here, it is valuable to be able to talk about whether something is or is not a game because that acts as one of these “rules” that then can be pushed, bent, or wielded by those trying to make games. For a fledgling designer, knowing that “Candyland gives no one any input or choice, and therefore it is not a game” is a very useful simple heuristic. An experienced designer can then carefully, cleverly, and wonderfully subvert that heuristic, as in games like Hot Streak and Magical Athlete (both of which are brilliant).

But should Candyland be dismissed as “not a game” in a way that implies no one should ever spend time with it? Definitely not. Is it worth the time of most of the board game audience to worry about this distinction? Probably not. Should Candyland be removed from the game section? Nah.

I am in 100% agreement with the idea that the dismissal of Candyland—represented by claims that it is “not a game”—is a deleterious thing that does not honor the real work of its design. The art, the setting, the simplicity and perfection of the rules for a kiddo. The fact that it means an adult can “play” to their “fullest ability” and still lose, giving a kid the chance to come out on top even against their parent! All of these things are valuable and deserving of praise and attention. Even its removal of agency is a masterstroke with regard to its core purpose—as a game for littles! You can bet your butt that Candyland is on my radar for my 2-year-old.

One more tangential example: for other professional reasons, I’ve been paying closer attention to the difficulty of writing a children’s book. Because on their faces, they seem so simple! There are so few words! You just need some cute art and a simple poem and you’re set! But that’s obviously so silly. There is an art to writing a good children’s book, and those who are skilled at it shouldn’t be diminished with the pejorative sense of “that’s just a kid’s book.” Simultaneously, though, those books shouldn’t be called novels. The writers of those books wouldn’t want them to be called novels. Novels are something different. They might all be books, but the differentiation of terms and forms is useful both to audiences and to creators…especially, then, when you can imagine a writer trying to play with those boundaries!

So maybe that’s the core problem. I think that games require agency (because if they don’t, then a tabletop game seems to simply be a procedure with physical components, even though putting together a Lego spaceship probably isn’t a game), but the truth is that it’s possible “game” is close to “book,” and I just want a way to refer to different kinds of “books.” Children’s books, novels, graphic novels, etc. If I want to call those Haba Games and Candyland “toy-games,” then I need another term for something like Ares Games’s War of the Ring, the game equivalent of a novel. And we need a short story term, and flash fiction, and so on and so forth. Some of those terms functionally already exist—”filler game” comes to mind.

But hopefully, then, the real point I’m trying to make comes through: that discussing what is and is not a game is productive, especially for those of us trying to understand and create new works in the medium, the same way that discussing what is and is not music can be valuable for the open-minded musician. “That is not music!” can be used as an attack to exclude something, but it can also be used as the start of an interesting discussion that might prompt whole new veins of music. It is a sad truth that this attack has been used, often in prejudiced or racist capacities, to try to exclude the new and the different, and I abhor that tactic. I have absolutely no interest in an exclusionary practice, a harmful denigration of works worthy of consideration. But talking about how The Beatles’ Revolution 9, a piece I have performed in front of an audience, is or is not music…that conversation can be fascinating and productive. I absolutely have an interest in asking where the boundaries lie, what the essentials are, and how all of it can be manipulated in skilled hands. So Candyland isn’t a game, to me, so much as it is a learning toy to use with my daughter…but it is a fantastic creation, and it does help me see better what games I might maybe, possibly, with luck, be able to make some day. I hope.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I really appreciate this thorough response. I don’t mind pushback at all. I’m completely open to changing my mind and enjoy deeper discussion. I’m sure many people who appreciate my work also don’t agree with every one of my reviews, totally cool.

There’s a lot to unpack here. I don’t have the time in the next few days to properly do so. You make some great points. I’d make a few in response though:

1. If a kid was taught Candy Land, Monopoly, how to throw a ball, and how to color, and then you asked them to sort them into categories of “Game” or “Not a Game”, I don’t think many at all would place Candy Land into the “Not a Game” category.

I wonder if the intuition of a child or less experienced player, someone not elbow deep in design and calloused with years of hobby theory, is actually less or more useful than the intuition of a game designer?

2. If I pulled 10 board game designers into a room and I asked them to decide individually whether Candy Land was a game or not, and then asked them why, do you think they’d all be in agreement?

3. Do you think Candy Land should be in the board game aisle at Target? Why?

LikeLiked by 1 person

(Just to be clear, I really enjoy and appreciate your work, and I absolutely always envisioned you as someone interested in the push and pull of discussion. Thank you so much for all that you do and for saying all that!)

Sorry to have dumped so much text! I hope it’s clear that I did it out of interest and appreciation. Love the questions.

I greatly appreciate talking about all these! I worry that my last answer is a bit of a cop out, but I think it helps clarify for me that context is king here. I really enjoy saying all of this in the context of a post named “Philosophy and Board Games,” but I would never say any of this to the kiddo in the aisle at Target. I will teach my 2-year-old that Candyland is a game, and I will not worry about sharing any of this with her until it can really torture her. Maybe when she’s 16.

So it might come down to this:

Apologies again for my prolixity, but thank you for providing the space and the interesting topic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No problem at all and definitely no need for the lengthy reply. I felt bad that I couldn’t offer an equally extensive reply to your comment. Very busy lately and behind on some things.

1. Concerning tamping down our intuition, this conversation is purely intuition as I don’t think you can make a scientific or evidence-based claim that games include meaningful decisions. So, I hear you, but I’m not sure that leaves us anywhere.

2. If the group of game designers wouldn’t agree on what is or is not a game, that lends creedance to the idea that we should defer to the widespread, less educated definition of “game”. For certainly, if the highest common denominator can’t agree, what real purpose is your working defintion that is proprietary? It would only cause more confusion. I would think you’d be better off saying “Candy Land is not a game with player agency” than “Candy Land isn’t a game”.

3. But this isn’t purely marketing. Imagine an archive placing old pieces of history in various sections. Or a library.

LikeLike

Totally fine to be busy! No worries about replying, I’m just enjoying the conversation.

I think for me, saying “Candy Land is not a game with player agency” reads confusingly, a bit like saying “this is a square without equal sides” or “this is a novel without words.” Though that last one is interesting—graphic novels exist! Can’t we have a graphic novel without words? In that case, the extra word is doing a lot of work in creating a new category that bears the traits of novels, while not being the same as novels. I’d love a new term like that, either for Candy Land-style works or for other “game” works, to help clarity. (Also, I think graphic novel is a term with a strong history in marketing, saying, “These comics aren’t just comics, they’re graphic novels!” If there were a commercial value in calling Candy Land a “toy game,” it absolutely would be called a “toy game” in every store where it is sold.)

If I’m in charge in these situations, I’m adopting the purpose of the situation. If I run Target, then sure, I could try to put Candy Land somewhere else than the games section, but…I probably want to sell copies, so I’ll put it wherever it does that best. Like an end-cap of a row, if it’s on sale. At which point, it isn’t with the games, but I don’t care, it’ll sell more. If I run the museum, then I’ll think about what exhibit I’m running, and why, and what it’s saying, before considering whether Candy Land goes in. If I run the archive, then I’ll think about the purpose of the archive and what fits inside it, as well as presumably practical matters—what’s my budget, how much space do I have. (Candy Land is certainly a less costly inclusion than, like, Frosthaven or Kingdom Death: Monster, both in money and space.)

Because I’m so harping on context, I can ultimately agree with this statement: For most groups of people who are aware of board games and Candy Land, Candy Land is a board game.

I definitely agree with this statement: Candy Land is worth appreciation as an impressive and valuable work.

Also, I am absolutely going to wind up getting Candy Land and playing it with my kid. Probably more than I expect right now.

LikeLike

Also, I swear, I reread to look for mistakes! I swear!

“A high-level physicist can talk about how gravity isn’t a force, it’s just the product of the curvature of the earth…but it doesn’t make sense to push that in context of a five-year-old who asks what makes things fall to the earth.”

“Curvature of spacetime,” not “curvature of the earth.” Clearly I know just enough about gravity to be dangerous.

LikeLike