Fobs Games put Tiefe Taschen out in the world back in 2016. It’s one of my favorite designs, uniquely presenting a tense affair of dynamic negotiation. It’s worthy of the word “brilliant”. By this virtue alone, I was interested in Gnomic Parliament. It’s the German publisher’s second release, arriving at the end of 2025. I was also eager to size it up as it contains a similar spirit to its predecessor. The primary parallel includes play occurring above the table in discussion and politicking. Sure, jolly gnomes quibbling over legislation isn’t as cool as corrupt politicians embezzling treasury funds, but the overall themes of corruption and egoism are compelling hallmarks of humankind.

The setting is relatively thin. The artwork and graphic design convey the cartoony gnome backdrop, but the majority of cards are simply text and the action occurs in the deduction and vocal sparring. At no point do I feel gnomish, which is fine. Preferred even.

What the game does do a solid job of conveying is an environment of awkwardly constrained political entanglements that can be hell to manipulate or overcome. It can feel as though you’re fighting the system more than the other players. On paper, this quality reminds me of a Cole Wehrle design aesthetic. In practice, this is more straightforward and can often land in a surprisingly unsatisfying way. This is almost entirely because the incentive structure is tuned in a very deliberate manner.

Let me set the stage for how it works.

Gnomic Parliament is a simple enough game from a rule standpoint. One player is the President, a role which can shift throughout the game if laws fail to pass. The President selects a law from an offer of three cards and announces their intentions of seeing it through. Everyone then chatters about this new legislation; ripping it to shreds or exclaiming its profundity. The group may debate the reasoning for selecting this law, or maybe how it will affect the dynamics of the game. Then everyone secretly selects their vote on whether to pass it or not.

The laws are a mix of clever and uninteresting. At their best, they wildly shape the contours of the game. And on the flipside, they do a whole lot of nothing while drawing a collective shrug. These laws are the core of the experience and define play, they’re the grist for the mill to chew upon. Some trigger one-time effects, such as awarding the gnome currently in last place a couple of victory points, or perhaps a point to a couple gnomes of the President’s choosing. More interesting are the permanent effects that alter the rules going forward. These can be delightful. One restricts the lead player from using lobby cubes, a resource which enhances the quantity of votes put forth. My favorite rewards a player two points if they are the sole gnome to vote “yes” on a law. There’s an opposite “no” version of this legislation as well.

These laws are taken from a large deck with just a subset randomly selected for a particular play. Session to session will see a small amount of overlap. I wouldn’t classify the quantity of laws as overly generous, nor meager.

The incentive structure is peculiar. Described as a virtue of the gnome setting, culture incentivizes parliament members to vote in accordance with their peers. This plays out as awarding a point if a player’s vote aligns with the majority. In the final rounds, the benefit jumps to two victory points.

At first this appears an interesting quirk. These majority votes constitute the bulk of end game scoring, as points are doled out parsimoniously in most sessions. This places strategy primarily in reading your opponents and extrapolating group vibes. Ride the wave and you will attain a slow trickle of points which will keep you within a gnome’s hair of the lead.

Unfortunately, what begins as a creative social puzzle in detangling incentives gives way to tepid group think. This system, fundamentally, penalizes radical behavior. It minimizes interesting plays, narrowing the scope of dramatic maneuvering. More often than not, nearly everyone votes one way, not wanting to risk going off the board and missing out on the precious majority point. The only way you can force an extreme outcome is by amassing many of those aforementioned lobby votes. Doing so can be difficult, however, and since they are limited to a single use, it’s rare to be able to shift momentum more than once across an entire 45-minute session.

The real tragedy here is that it feels as though players have little social recourse. The primary reason to want to tip the vote one way or another is to manage which players receive points. If someone has a clear lead, for instance, the table really needs to vote in a way which cuts them out. Maintaining status quo and stumbling towards the end game is folly.

But I can’t speak up and try to form a new coalition to oppose an existing majority and cut out the player in the lead. If the tone begins to shift too far and I’m too overtly convincing, everyone will just flip sides and the situation won’t change. What’s important to understand here is that the laws themselves aren’t terribly important in terms of motivation. Laws don’t target specific players too often, instead altering the game-state in an egalitarian fashion. Individual players typically won’t feel strongly about a law that limits lobby votes or offers bonus points to players who vote no. Everyone can benefit equally for the most part, and the stakes for any outcome hinge entirely on joining the majority and getting that precious point. It can feel as though the game is hobbling itself, muzzling interesting discussion. The outcome, then, is either random voting or everyone piggybacking on each other in an odd crabs in a bucket-like situation.

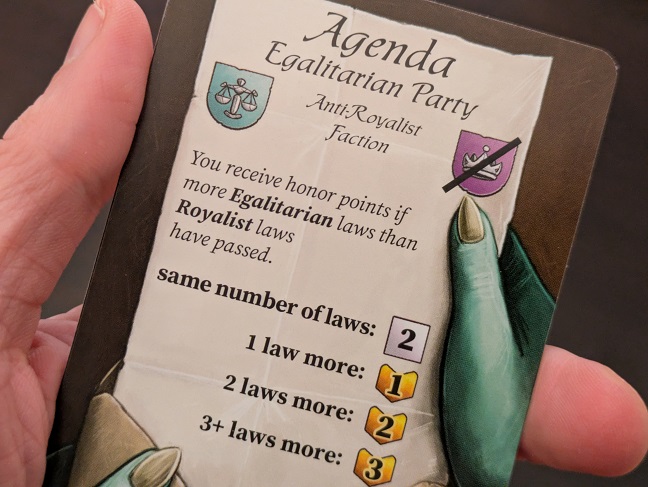

The advanced mode improves the game somewhat. It adds hidden agendas where you want laws of a certain suit to pass and another to fail. You’re also dealt a neat personal law which can be used instead of selecting one from the offer when you’re President. These cards are very powerful and give the game a huge shake. Sadly, they’re rarely used as often they don’t align with your goals and can even be a net negative in certain circumstances.

Hidden agendas, much like the game’s incentive structure, are wonky. The law cards that comprise the main deck are randomized. This means sheer probability will favor some players, as more of the suit they care about will be present. The degree to which you take a 45-minute game about gnome government seriously dictates how much this will bother you. With that being said, it’s proven annoying to a meaningful number of participants in my experience. Additionally, as long as everyone is strategically capable and aware of the game-state, the mixture of suits in the passed laws is often manipulated as a group to artificially even out. What I mean by this is that if a couple of red laws have already been passed, people will start advocating to vote down future ones so that those with the red agenda do not benefit. This results in a typical outcome of a single point or so being awarded to most players for objective scoring. Overall, these add a nice little wrinkle to the incentive structure and discussion, but their implementation is askew and the outcome not terribly meaningful.

Some of Gnomic Parliament’s issues are ameliorated at the highest player counts. It’s a little more difficult to suss out the collective vote when there are eight players sitting at the table. This, combined with the advanced ruleset, achieves the highest probability of an intriguing session. But even less one or two squirrely gnomes, too often there’s virtually nothing you can say or do to shift the social impetus. You can try to speak vaguely or push people into assessing multiple layers of bluffing, but you’re hoping for a particular result instead of deftly steering the game towards it. And if you get it wrong and vote off majority? Well, then you may lose the entire game as a consequence of that one bad play due to how close scoring is and how few ways there are to achieve significant swings.

One thing which would help this game would be wilder and unhinged laws. It needs more ways to shakeup scoring, as it’s far too coarse in the current configuration. A more dynamic leaderboard or even more obnoxious and impactful legislation would grease the social element. The particular thing being voted on is far too often irrelevant, and the result is harmed.

Overlooking the flaws for a moment, it is useful to examine the game’s unique themes. There’s a philosophy of collectivism embedded into the design which, on its own, is provocative. The restraining of individualism lends a certain tone that clashes with the standard competitive zero-sum experience. Yet, I’m not sure how much value should be placed in any inherent message ingrained in the design, for it’s not outright extolling the virtues of unity. A single player wins regardless of cooperation. If anything, it paints an ugly picture of the effort required to upset tradition.

I wish it went harder on those themes. This would have shifted perspective somewhat on the rest of the design.

Really, I’m just bummed. Tiefe Taschen is such an exemplary tabletop design, one which should be celebrated. Gnomic Parliament is not awful by any stretch and I have had bursts of elation with it, but they’re spread too thin as the very foundation of the game is cockeyed. It’s possible certain groups may approach from a more carefree perspective and not drive so hard into the incentive structure. I don’t think that would nullify my criticisms, but it may make them less evident. I’ve struggled with the idea that anticipation may have unfairly altered how I view and assess this game, but I’ve done everything I can to make that not so. I do not think it’s the case. Despite my best wishes, I can’t will Gnomic Parliament into success.

A copy of the game was provided by the publisher for review.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon. No revenue is collected from this site, and I refuse to serve advertisements.

A pity! It looked so interesting, but I see how the steady trickle of points from majority-voting can be too good to resist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, it’s a shame. I’ll be curious to see how others feel about the game. Hopefully it gets out there and gains some attention.

LikeLike