“Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

It’s the early 90s. With utmost care, I slowly creep around the rotting shed that dominates the far side of the yard. The tiny fuzz on the back of my neck bristles.

I approach the corner of the structure and press myself against the wall. The only sound is the flaking paint crackling against the pressure of my back. In my hands is a rifle. You see a hockey stick, but I see a rifle. My fingers are wrapped so tightly around the barrel you’d need a crowbar to wrestle it from my grasp.

I breathe deeply. I think of the movies my dad watches, the glimpses I’ve stolen of large men doing large deeds. I spin around the corner in a flash, pointing the muzzle at my brother. I yell BAM with enough fury to let the block know I’m doing war.

War has always held my attention. It seems primordial, something I can’t divide from myself. I’ve tried to counterbalance this preoccupation with a strong affection for moral philosophy, but the truth is that I’ve seen Apocalypse Now many more times than I’ve read The Metaphysics of Morals.

I don’t want to just watch combat. It’s akin to a terrible automobile accident I drift by on the interstate, slowing down so I can satisfy my curiosity with a flash of carnage. But I also want to be inside the vehicle. I want to be tossed across the pavement in a metal cage and feel death crack through the air. I want percussion to batter me. I want to display courage under duress. I want to be in the shit.

Bernard Grzybowski’s Purple Haze is a Vietnam War game infatuated with personal stories. It’s much more The Things They Carried than We Were Soldiers Once…and Young. This is a narrative-focused design, one that hearkens back to Avalon Hill’s Ambush! Although it’s more modern and precise, carefully designed to elicit an experience that trades the baggage of mechanisms for that of emotion. As an immersive and intimate experience, it’s totally captured my lust for war.

This is a campaign game, one where you take a squad of six soldiers through nine missions, attempting to keep their souls and bodies whole. It’s an unlikely task.

The campaign begins by drawing your men randomly from a large pool. You must fill each position – RTO, gunner, medic, etc. – from just a few selections. Characters have ratings in several stats, similar to the personalization of a traditional roleplaying game. Optimization is nearly impossible. Tradeoffs abound, such as my choice of infantryman Lee Brown to haul the M60. His affinity for survival and superlative awareness makes him a solid candidate, but unfortunately, he can only haul 10 units of gear. This means he’s only able to take the light machinegun and limited ammo. Consequently, he will go without a flak jacket, grenades, or extra rations. I make do, assigning an additional belt of MG ammo to my engineer Hopper to lug around. These difficult decisions are the core of this phase and later serve as springboards for drama.

While the squad persists across the length of the campaign, you’re able to change the assigned gear prior to each scenario. The system utilized is simple and effective. I find it an excellence compromise between abstraction and detail. It reminds me of the excellent Warfighter series from Dan Verssen Games. Both titles feature a loadout phase which is of great consequence to how the mission will play out. While this may sound like cumbersome administrative work, it’s actually of minimal effort as you will quickly develop useful heuristics and preferred setups for each specialization.

The most integral aspect of the equipment system – and what makes the limited housekeeping worthwhile – is that you can feel the weight of your squad’s burden. As you expend effort trying to min-max each point of gear, the frustration of bulky firearms and unwieldy radio units is driven home. It primes you for the ensuing deployment, underscoring the fatigue and travel mechanism with gravitas.

Several years have passed. I’m too old to be playing with pretend guns but I’m doing it anyway.

John is my best friend. His yard is no yard at all, it’s a moon littered with craters and the dead. I’m holding a nerf gun, but if you squint and back up a little ways, it looks just like a bolter. John has a Super Soaker, except we both know it’s a flamer.

We leap out from behind a makeshift barricade, the detritus of sports paraphernalia, bicycles, and yard furniture won’t hold much longer. We have to make our move. I remember Jeff Daniels at Little Round Top. I use every inch of my lungs to yell CHARGE!

You can’t see them, but the horde of Genestealers and Termagaunts wither under the force of our courage. My eyes are wide and my heart is raging.

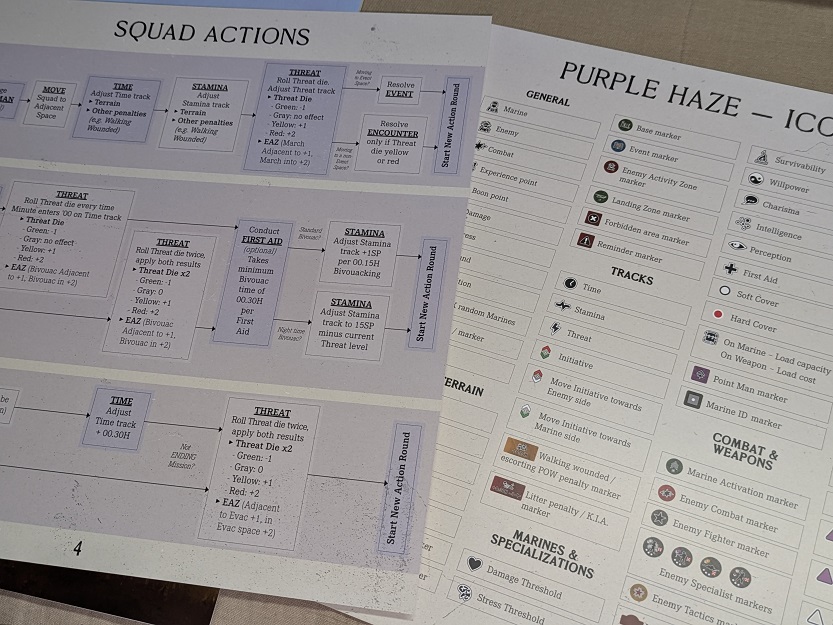

Humping cross country is an ordeal. Each space is designated a different type of terrain, with onerous topography burning more of your squad’s stamina and time. Stamina is important because if you push too hard you will need to rest, bivouacking for a short period and eating up more daylight. Time is crucial because missions often require you to hustle and meet a deadline. There’s also the concern of nightfall, where danger spikes and firefights become more chaotic.

Threat is the final consideration. It represents an abstract measurement of danger in the area. A die roll determines whether it escalates with each movement on the map, and if it grows too severe it will often trigger a particularly nasty encounter. The intersection of all of these variables provides context for the developing storyline, and it creates emergent dramatic interaction.

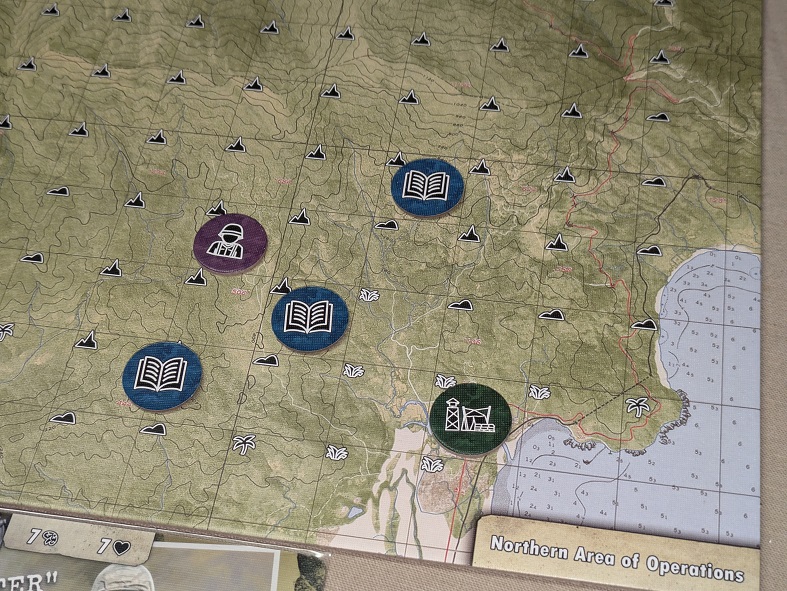

This strategic macro portion of Purple Haze is where you will spend roughly a third of your time. It’s surprisingly slim, requiring little rules overhead and facilitating brisk play. You can move your squad token to an adjacent space, roll a die, and shuffle markers on a couple of tracks in a matter of seconds. The board itself is depicted as an operational level map of the region, which instills the sensation of a commander untangling a SITREP and planning the best course of action.

Most of the board is barren, the only features being the various types of terrain such as jungle or mountains. A few tokens will be placed at specific coordinates dictated at setup. This usually includes your base and numbered points of interest. Typically, your objective includes patrolling certain areas or interacting with placed event markers. The generic tokens are utilized in creative ways and provide the propellant for story.

Contrasting with the macro view of overland travel is the personal narrative. This is the identity of Purple Haze and where its various themes emerge to form gut-wrenching war stories. Like the rest of the design, this element is a combination of multiple interconnected pieces.

Event cards are the more direct embellishment. These oversized cards present a narrative description, along with either a direct outcome or a required test against one of your squad member’s stats. The dice system is, well, funky. Let’s put that on hold for a second.

The more distinct and elaborate story component is the mission booklets. Each scenario has its own bespoke softcover manual with a thorough introduction, mission parameters, and numbered entries referenced at appropriate times during play. This is what I think of when I meditate on Purple Haze. It’s the heart of the experience. The paragraph system is what links it spiritually to Ambush! and it’s how the bulk of drama and wonder is delivered.

Like the travel system, it’s surprisingly restrained. There is a solid amount of text and the writing is adequate for this style of story, but the actual systems involved are accessible. Many paragraphs may interact or effect the macro stats of time, threat, and stamina. Often, you will be presented difficult choices, some which challenge your moral framework. Sometimes you will be asked to note a keyword which may influence later encounters or your graded performance at mission conclusion.

There is quite a bit of branching structure overall, and it feels as though there are several pathways through each scenario. Most encounters are written with explicit flexibility, so you’re not required to trigger paragraph entries in a particular order. There are some neat editorial decisions that remind me of the investigative classic Gumshoe, in that arriving at some scenes at a specific time or with a certain keyword will drastically alter what you encounter. This approach adds a sense of authenticity and depth to the environment, qualities which prop up the narrative component of play. It also reincorporates previous details which supports a cohesive story structure.

The flow is the most interesting quality of Purple Haze. You will transition from map travel to event card, back to the map, and then to the mission book for a paragraph. This is all relatively seamless and systems feed into one another, often creating provocative outcomes and situations.

And just as you’re humming along, feeling the insects biting at your flesh and the sweat collecting in the folds of your battle dress, a punji stake finds the soft flesh of your foot. I’m talking about combat. That’s the punji stake.

I’m very conflicted on the combat system. From the perspective of game design and its intentions in the game loop, I think it accomplishes its goals adequately. It provides a jarring changeover in game state, zooming in to the battlefield where each individual soldier is represented by a token. It’s tense, as this is where your men are most likely to be broken and beaten down. Every decision feels consequential, particularly because you’ are’re only allotted a single activation for each grunt before the battle ends. In terms of simulating time, these firefights are brief skirmishes flush with peril.

My hesitation in rubber stamping this sub-system is that it’s much more complex than every other facet of the game. There’s hard and soft cover, line of sight, various grenade resolutions, multiple firing solutions for various weapons, artillery support rules, random event tokens, a really clever action point system, and a pretty unusual dice methodology.

Some would call the dice resolution weird. I appreciate it, perhaps for its irregularity.

When taking stat tests or firing weapons, players roll handfuls of six-siders. Purple dice set your target numbers, while white dice count as successes. For instance, when shooting the iconic M16 you roll two purple dice and four white. If the purple come up a 1 and 4 and the white results are 2, 4, 4, and 6 – you’ve scored two hits due to the pair of fours matching the purple die of the same value. There’s more to it than this. Duplicate white dice that don’t match a purple die can substitute a white as a purple. It’s wonky, yeah. There are also yellow dice which score additional hits. Oh, and there’s a critical effect which can be difficult to remember during the frenzy. Scouring online forums reveals that there are more than a handful of players totally confounded by all of this. I don’t blame them as it’s not intuitive.

I’d describe the dice mechanism as dirty. It’s difficult to immediately parse the outcome with larger rolls. It’s also somewhat impossible to intuit probability in a satisfying way. I tend to appreciate that element in systems, as it reduces the sensation of number-crunching and min-maxing in the midst of play.

All of it works coherently, and it’s certainly captivating. Unpredictable results emerge out of the chaos and attention hinges on every roll. It feels hectic and even grueling in the best of ways, as I all too often wince when resolving the opposing counterattack.

When considering the entirety of the combat mini game, I’ve never been so indecisive about such a central mechanism. There are gnarly inclusions like the back-and-forth action point track, as well as the tough decisions on who to activate and in what order. Characters feel brittle at times, and often you must carefully split your actions between supplying firepower or digging in for cover. Weighing risk versus reward is imprinted into every inch of Purle Haze.

There are a couple aspects of combat which act as a gravitational force to keep me even keel. One nagging sensation is that it’s a little too regimented in terms of battle formations. Your GIs setup on one side of the board while the Vietcong are placed on the opposite. A dividing line separates the two forces, creating a feel of a pitched battle. This is not emblematic of the type of guerilla tactics found in jungle firefights. It’s a clean team-versus-team format and you can clearly make out your targets. The dice-system, cover effects, and severe outcomes of taking fire do sort of patch over this blemish with some needed delirium, so it’s not completely shattering.

The second issue is perhaps more expected, in that setup is a little painful. You can spend a good five minutes placing tokens in the right space, double checking positions as displayed in the scenario book, and then organizing yourselves for battle. And then the whole firefight is wrapped up and completed in just 10 more. Much like the previous issue, this isn’t too compromising, but it’s unfortunate and undermines some of the narrative’s momentum.

Thus, I’m conflicted overall. The system is reasonably effective, and it certainly produces moments of intensity that are utterly memorable, but at the same time, I occasionally find myself flipping to an entry in the mission book hoping to find text as opposed to a battle diagram. That sensation undercuts my desire for endorsement.

I’m sitting in a chair, staring at a screen. I’m older now, but I still spend my summers in conflict. My weapon is a mouse and my mechanization is by modem.

With each forceful click another Nazi dies. I smile when the clip ejects from my M1 Garand and that sweet ping sounds.

A television in the background is playing Saving Private Ryan. The DVD doesn’t leave the player for months.

Purple Haze is an entertaining and gripping affair. What sends it over the top is its ability to manage an anti-war stance with sincerity and skill.

Steven Spielberg famously said, “every war movie, good or bad, is an anti-war movie.” This is not true in the wargame hobby. Combat Commander is not anti-war. Advanced Squad Leader is not either. Fire in the Lake? Almost but not quite. These various titles – as well as nearly the entire catalog of historical wargames – adopt perspectives of cinematic action, strategic logistics, or navigating the politics of complex alliances. Some brush up against elements of morality, such as Fire in the Lake’s tension of air strikes versus capturing hearts and minds. None of them commit wholly to the horror. The violence is abstract and often faceless. It may as well be on the other side of the globe.

In ignoring the moral side of armed conflict, wargames may be doing us a disservice. They can glorify bloodshed and elevate the appeal of otherwise heinous acts.

Things change.

The first time I committed a war crime in Purple Haze, I was gutted. It was accidental, but that offers no absolution. I have to live with that decision, and it would hang around my neck in the form of psychological damage.

There are two types of traumas in this game, physical and psychological. The former can come in bunches, either delivered via narrative entry or within the confines of the battle system. The latter is almost explicitly inflicted as a result of story decisions.

The brilliance here is that the shredded flesh and broken bones heal over time. The worst of the bunch, ignoring KIA results obviously, require your soldier to be hospitalized temporarily.

Psychological trauma almost never heals. Occasionally you can reclaim some lost sanity through altruism; those beautiful moments where humanity breaks through your warfighter’s hardened exterior. But for the most part, that mental degradation hangs around, a constant reminder of the pain you’ve suffered and inflicted. Like the various tokens of gear weighing down your soldiers, these cognitive damage markers stack upon the character and clutter up their identity.

Punches are slightly pulled. The worst of the worst isn’t depicted, but civilian casualties, as well as green on green violence, is certainly a core element of gameplay. This instills the raw terror of the Vietnam War and presents it as a cruel and futile conflict. While I feel a tinge of guilt when bombing population centers in strategic level wargames, Purple Haze hits different. It’s a sanitized take on the Oliver Stone period drama, but it absolutely portrays a similar motif, challenging your moral framework with an emotional salvo.

It’s important to set expectations correctly. While this is a narrative game, the stories are not incredibly complex. Purple Haze addresses some of the same themes as Stone’s war films, but it is not capable of capturing nuanced intrasquad dynamics such as the feud between Elias and Barnes in Platoon. Yes, it’s more sophisticated than Ambush!, but it’s not the carefully scribed story of Tainted Grail.

The majority of story is also not mired in ethical conundrum. There’s a lot of patrolling, a lot of overcoming obstacles, a lot of tough strategic decision-making regarding mission approach. One shouldn’t think of this game as primarily framing moral dilemma.

Instead, Purple Haze presents these moralistic challenges as crescendos in a blended narrative wargame. This is precisely the genre work I crave at my current age, the type of thing that allows me to play guns while still facing moral consequence.

War has held my interest for nearly my entire life. I don’t know exactly why. It’s not something I’m proud of.

I desperately want to fight for something greater than myself. I want to overcome fear. I want to prove I’m not small and weak. I want to be brave. I want to be brave.

The fundamental immoral nature of war is a contradiction to this desire that will forever trouble me. Looking at the current state of the world only highlights how misguided and tragic these thoughts are. I don’t know what to do with that.

Despite, or perhaps because, of all this, Purple Haze is an opportunity I can’t help but seize. Its compelling conflagration of systems results in elevated output that’s branded on the player’s psyche. Or at least, it’s been branded on mine.

Many more years are lost. I’m sitting in a basement, alone.

One of the LED tubes on an overhead lamp has burned out. Fortunate Son is playing from somewhere.

The squad has just traveled across rough ground. Tey’re weary as hell. I crack open the booklet nervously, squinting to read the text and determine their fate.

“Ahhh”, I groan in despair. But I’m the only one listening.

Like a dope, I followed the footprints right into a kill zone. Charlie is ambushed by Charlie. I reach for the dice and clench them with all the nervousness of a seven-year-old boy playing war in his backyard.

A review copy of the game was provided by the publisher.

If you enjoy what I’m doing and want to support my work, please consider dropping off a tip at my Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon.

Great review. How would you compare this to War Story: Occupied France? Did you play solo? Is one title better suited than the other for multiplayer play?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good questions. I didn’t talk about player count because I only played solo and can only speculate on increases numbers.

Was Story is more of a Choose Your Own Adventure game with some neat twists. It’s almost entirely text driven. Purple Haze feels broader mechanically because you have overland movement with text being triggered at certain times. There are more pieces and details involved.

I think both probably work best solitaire. Both seem as though they would work with cooperative play, but there is not a lot of activity to split between the players. So it’s mostly about making story decisions together and collaborating.

LikeLike

FWIW as the developer of Purple Haze, I think the best player count for it is two, with one of the two – not the player managing the Squad Leader – managing the text and Encounter cards.

With two you feel even more ownership of your three Marines, which is great for micro narratives and relationships between the Marines to emerge; and you have more mental bandwidth esp during combat as less individual skills and abilities to remember.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece, Charlie. I too, have a life-long fascination with the history of war and war gaming, and have never been able to square that fascination with the deeper moral issues surrounding war. Thanks for voicing your own struggles. I’ve never heard anyone else voice them aside from gaming friends who won’t play war games at all because of the subject matter.

Quick question – Do you have any opinions about the many expansions?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Carl.

Unfortunately, all I have is the base game. I may buy the expansions at some point, but no promises there.

LikeLike

Thanks for the review Charlie, really interesting and I like the personal reflections.

I’ve enjoyed comparing it with Space Biff’s review too, both different, both insightful, giving me more to think about than the reviews would on their own.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Greg! Dan’s review was excellent and a pleasure to read.

LikeLike

That was a very insightful review 🙂 As a guy who wrote those missions for Purple Haze, I’m really glad to have found a review noticing the anti-war themes in the game. I’m of mixed ex-Yugoslav/Polish nationality (incidentally, the author of Tainted Grail’s story is also Polish, how odd is that?), and the Yugoslav Wars have always had an impact on me, at least in the way I look at war – and I put some of how I feel about it in this game. To be clear, once I got on board this project, my intention was always to show the war from the individual Marine’s POV rather than, for example, delve into the politics of it all, plus the game came with mechanics that allowed me to do it more viscerally (I hope, I’m definitely not the best judge of my own work ;)).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your work and putting some of your own experience/perspective into it. It’s a fantastic game.

LikeLike